February 2026: The Movie That Was Never Made: Lessons from Dot.Com for the 2026 AI Era

February 2026: The Movie That Was Never Made: Lessons from Dot.Com for the 2026 AI Era

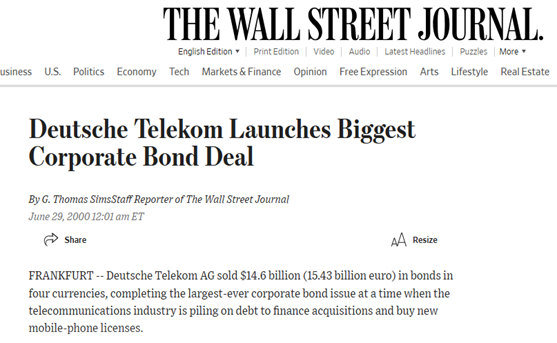

When I think about our current moment, I keep returning to the late 1990s and early 2000s—the Internet boom and the bust that followed. Thinking about Google’s multi-tranche, multi-currency bond issue last week got me thinking about this Deutsche Telekom deal in 2000. The Deutsche Telekom bond issue – largest corporate deal in history at the time — triggered a younger me to reappraise Internet stocks and cash out (a good decision).

We have It’s a Wonderful Life, The Big Short, Margin Call, Too Big to Fail, and other films about key financial events, but there’s never been a major movie about the Dot-com era. Regular Treasury Talk readers know that I love using movie references in my columns – but I could not find a single Dot.com movie. Perhaps because technology is difficult to dramatize? Yet the lessons from that period are strikingly relevant today as we navigate the artificial intelligence (AI) boom in 2026.

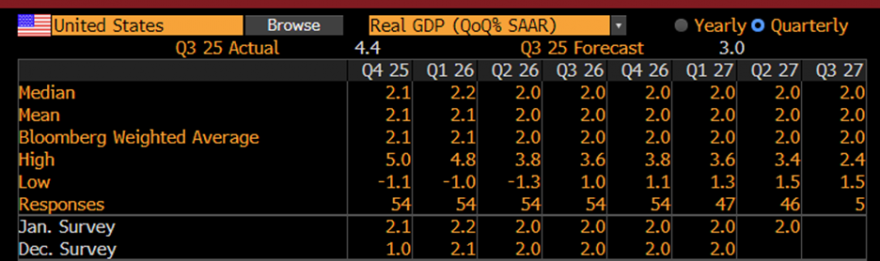

The parallels are uncomfortable. The market’s complacency about three critical risks is concerning. As I write this in mid-February, fresh data are starting to reveal economic acceleration that challenges the consensus narrative of steady 2% real US GDP growth with continued steady disinflation over 2026.

The Greenspan Playbook Revisited

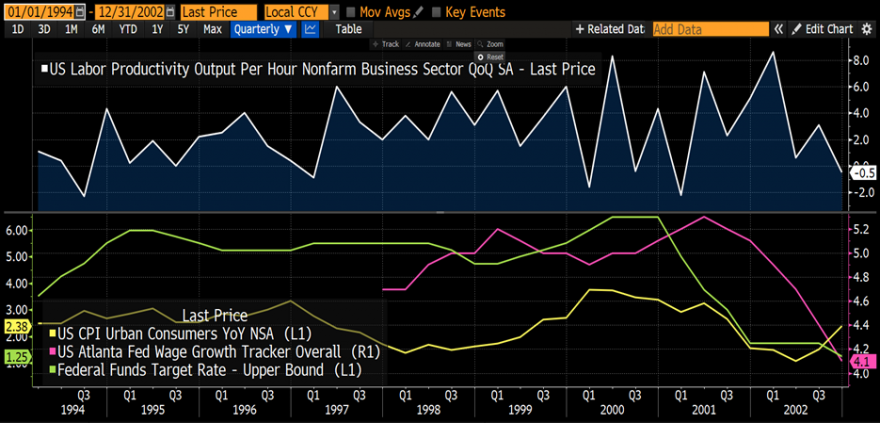

Let me take you back to a policy decision that shaped my early working career. In the mid-to-late 1990s, Fed Chair Greenspan faced a decision that now in 2026 has become a bit of folklore. The current popular narrative about this period is simple and seductive: productivity was rising due to Internet adoption and digital transformation, so the Fed should cut rates into this “productivity shock” and let the economy run hot.

But here’s what the data show: productivity (the white line) was indeed rising during the Dot.com period. However, inflation (the yellow line) was already above target when Greenspan cut rates anyway—from 6% to 4.75% (the green line). What followed: wages rose (the pink line), inflation re-accelerated (the yellow line), and the Fed was forced to raise rates to 6.5%. One year later, the Dot.com bubble burst and the U.S. economy entered recession.

Now, as we prepare welcome new Fed Chair Warsh, there’s talk of reviving this playbook for the AI era. The question we should be asking isn’t whether AI will deliver productivity gains—it likely will, eventually.

The question is: can we afford to bet monetary policy timing the arrival of AI productivity gains perfectly while simultaneously running accommodative combined fiscal and monetary policy outside of a recession and with the US labor market historically supply constrained? Given my framing of the question, I think readers can discern that I would say “no.”

Fresh Data Shows Acceleration, Not Slowdown

Last week provided several important data points that the market hasn’t fully digested. Treasury Secretary Bessent noted that US tax refunds were up 22% relative to last year due to OBBBA. This matters enormously—the rise in this cash component of the U.S. budget deficit is very important to aggregate demand acceleration. When households receive larger refunds, they spend them, adding fuel to the economy. US companies also may take the opportunity of tax refunds to pass along 2025 tariffs to US consumers.

Then came last week’s employment report, which surprised significantly to the upside and started to show the economic acceleration that I have been writing about. Yes, some observers latched onto downward employment revisions (mostly in late 2024 and early 2025) and noted the concentration of January job growth in healthcare. But look deeper: there was clear evidence of job growth in other areas of the economy starting to gain momentum, including manufacturing. This isn’t an economy that needs more stimulus—it is an economy that’s already accelerating.

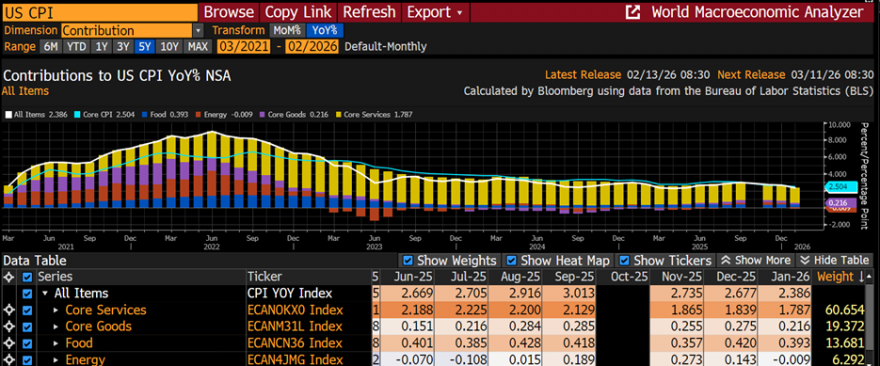

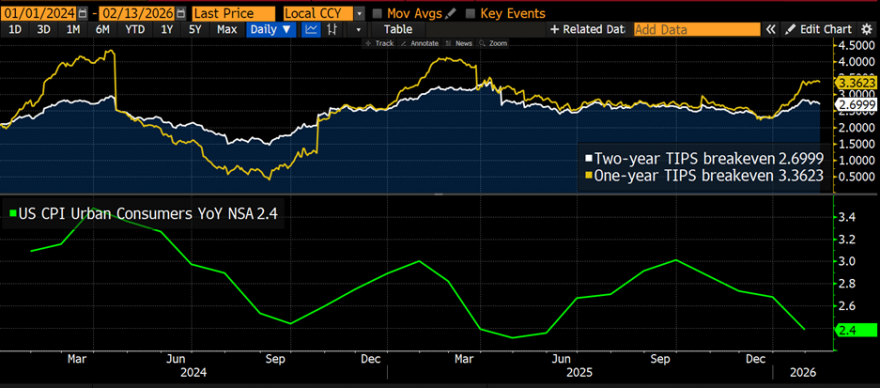

Meanwhile, the market drew too much comfort from last Friday’s January CPI data, which came in slightly below expectations. The market breathed a sigh of relief and the Fed funds futures strip now suggests two Fed rate cuts likely and maybe even a third rate cut in 2026.

But January US CPI doesn’t yet reflect the rise in oil prices we’re seeing now, nor does it capture the demand acceleration that’s underway. Further declines in CPI is unlikely to remain an enduring trend over the next few months, in my view.

Risk #1: Fiscal and Monetary Stimulus Amid Labor Supply Constraints —A Recipe for Overheating

Here’s what has me worried: we’re currently experiencing fiscal and monetary policy easing simultaneously—a potent policy combination that should be reserved for recessions.

The OBBBA fiscal boost in the first half of 2026, combined with Fed rate cuts and rate cuts from central banks in the rest of the world, is creating significant stimulus. More defense spending and stimulus appear to be coming. The risks to the consensus/median view on U.S. growth and employment are decidedly to the upside.

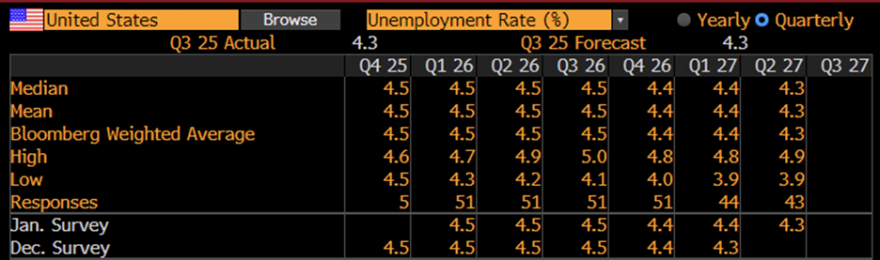

But here’s the critical constraint: significant changes in US immigration policy are reducing the size of the U.S. labor force. Job growth may look weak in the headlines, but that masks what’s really happening with labor supply. Census and population data are updated slowly, making it difficult to gauge labor supply in real time. We’re in uncharted territory, and that means labor market conditions can turn tight very quickly. Again, the consensus does not show that.

Think about what this means: we’re adding significant combined stimulus to the US economy with a shrinking labor force. Two things drive economic growth—labor force growth and productivity growth. U.S. labor force growth has stalled or turned negative due to immigration policy and demographics. That leaves us looking for technology-enabled productivity growth to deliver a non-inflationary expansion.

Which brings me to inflation where I see significant upside risks to the consensus/median view that US inflation is coming down.

Why are inflation and “affordability” risks skewed to the upside? Multiple factors:

-

The combination of fiscal and monetary policy easing;

-

Tight labor supply;

-

Delayed tariff impacts yet to fully arrive;

-

Energy price disinflation over; oil prices beginning to rise; and

-

Long-run inflation expectations rising due to higher prices of high frequency/ real-world items—groceries, healthcare, electricity.

2 year TIPS brekevens are up almost 100 basis points since January.

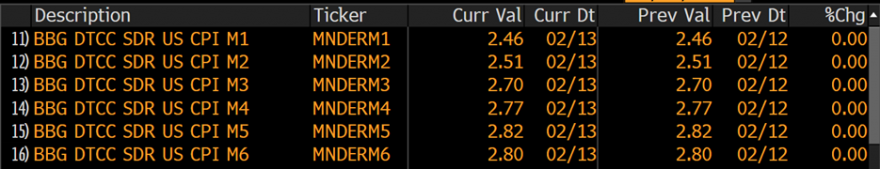

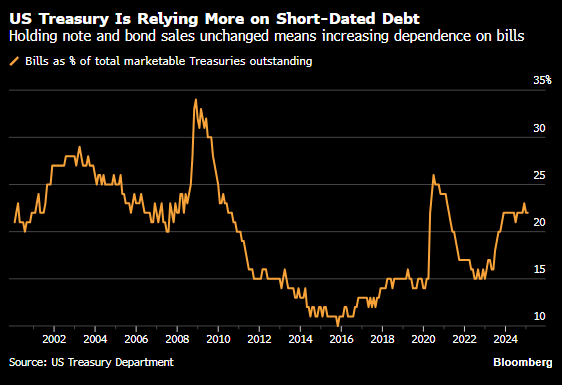

CPI fixing swaps suggest headline CPI will rise over the next six months. Inflation markets are starting to get it, but I don’t think the risks for late 2026/early 2027 are fully appreciated or appropriately priced more broadly in markets.

Risk #2: AI’s Promise vs. AI’s Reality

AI data center investment, electricity and water demand are significant, adding to inflationary impulses. AI investment is estimated to be 2x larger in inflation-adjusted terms relative to Dot.com cap-ex spending. The largest U.S. tech firms have planned $660 billion in capital expenditures for 2026 alone, primarily for AI infrastructure. AI significantly boosts demand for aggregate investment relative to aggregate savings, putting upward pressure on interest rates.

At the same time, AI stocks largely are still priced as growth stocks—high multiples justified by expectations of rapid revenue growth, strong free cash flow, and robust share buybacks. But these companies are transforming into cap-ex heavy businesses with less attractive cash positions to support share buybacks. The $660 billion in annual cap-ex doesn’t just disappear—it either comes from cash on hand (reducing buyback capacity) or from debt issuance (increasing leverage and interest expense).

And what near-term productivity are we getting from this massive investment? The latest Richmond Fed/Duke CFO survey suggests not much. The majority of CFOs report seeing no productivity impacts—or any other measurable impacts. Let me repeat that: we’re in the midst of a $660 billion AI investment boom, and most US CFOs aren’t yet seeing the benefits.

On a related note, an ongoing Yale Budget Lab study on AI’s impact on the U.S. labor market tells a similar story. While the mix of U.S. occupations is changing more quickly than in the past, these changes in the US laborforce appear to predate AI adoption. The Yale team’s work suggests that changes in both U.S. employment and unemployment appear unrelated to AI so far.

Even the occupational mix between recent U.S. college graduates and older college graduates shows little change, suggesting limited impact of AI on youth employment thus far.

Thus, AI is unlikely to substitute for the shrinkage in the U.S. labor force due to immigration policy and demographics—at least not in the timeframe relevant for monetary policy decisions in 2026 and 2027. This situation skews inflation risks to the upside.

And here’s the risk that should concern every bank treasurer and chief risk officer: if the overall productivity benefits of AI fall short of expectations, a U.S. macroeconomic shock and fall in U.S. asset prices will ensue. Easy fiscal and monetary policy may be enabling over-investment in AI. The bigger the investment boom built on excessive official sector stimulus and optimistic assumptions, the bigger the potential bust.

Risk #3: Fed Behind the Curve by Late 2026/Early 2027

This brings me to my third concern: the Federal Reserve risks finding itself behind the curve by late 2026 or early 2027. The combination of fiscal and monetary stimulus, shrinking labor force, delayed tariff impacts, and the end of energy price disinflation creates overheating risks that pose significant upside inflation risk. “Run it hot” sounds appealing in theory, but it’s a dangerous gamble in practice.

If inflation re-accelerates in the second half of 2026 as I expect, and if AI productivity gains remain elusive in the near term, the Fed will face an uncomfortable situation remarkably similar to what Greenspan confronted in 1999-2000 and that will be negative for financial markets and the US economy.

The policy response – one would hope — should be predictable: rate hikes. But by the time the Fed pivots, financial conditions will have been loose for an extended period. Asset prices will reflect optimistic assumptions about AI productivity, low inflation, and continued monetary accommodation.

For bank treasurers and credit officers, this is where one of the oldest lessons in banking becomes critical: the worst loans are made just before the economy turns south.

Loose fiscal and monetary policy combined with deregulation is supporting not just AI growth, but risk-taking in the financial system.

The Structural Challenges Continue to Build

At the same time, the longer-run U.S. budget deficit and public debt stock have been allowed to grow too large over decades. We’re now seeing the consequences:

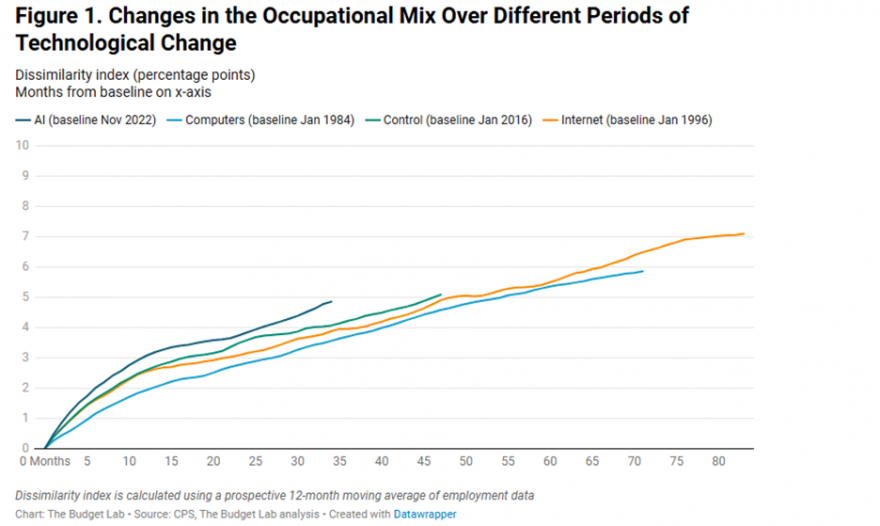

The 10-year 10-year forward Treasury rate and 10-year Treasury term premium are both rising even as the Fed cuts rates. This is unusual and a worrying trend that suggest investors are demanding higher compensation for holding U.S. government debt over the long term.

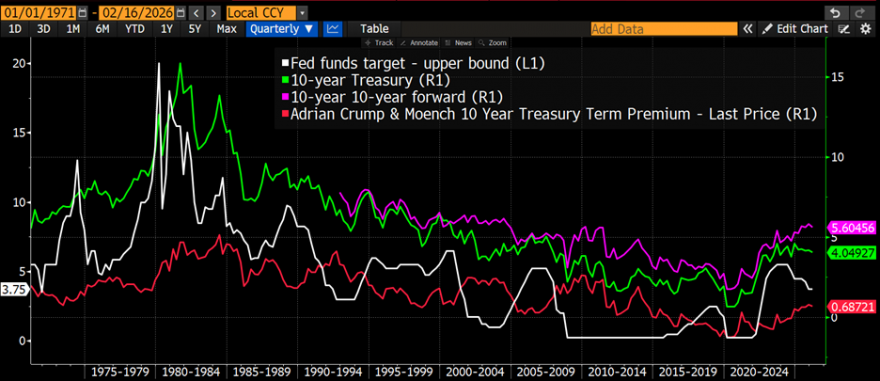

Treasury’s response to these structural challenges has been to increase reliance on T-bills—short-term funding that creates pressure on the Fed to lower interest rates and also to conduct debt buybacks. While some may note looking at the chart below that the T-bill share has been higher, high T-bill shares after 2008 and COVID reflected initial Treasury borrowing responses to large shocks.

2013 BIS research that I have my fixed income students read suggests that the high T-bill share in 2004-2005 drove long-term Treasury rates down and contributed to inflating the U.S. housing bubble. Could a shortened Treasury weighted average maturity (WAM) also contribute to inflating the AI bubble now?

The Fed’s Balance Sheet Problem Persists

Meanwhile, Fed Chair nominee Warsh is interested in shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet. While I agree that the Fed’s balance sheet has been allowed to grow too large since 2008, we keep making the same mistake: trying to shrink the Fed’s balance sheet without first fixing the underlying plumbing and strengthening bank Treasury. I wrote about this problem in detail in my recent American Banker op-ed out last week (https://www.americanbanker.com/opinion/feds-balance-sheet-problem-fix-the-plumbing-first ), where I argue that several critical reforms need to happen before another attempt at QT:

-

The Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility needs to be closed

-

Treasury should lend out its excess cash balance to banks rather than holding it at the Fed

-

The primary budget deficit needs to shrink to reduce pressure on banks for repo financing of Treasury issuance

-

Fed discount window operations need improvement

-

Supervisory expectations on bank liquidity and interest rate risk need a reset, especially given $340 billion in unrealized securities losses at some banks that makes them dependent on Fed liquidity.

Shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet without addressing these issues risks compounding prior Fed errors and could create new strains for bank treasurers.

The Stablecoin Gambit

There’s a new twist in Treasury’s funding strategy: the Administration hopes that USD stablecoins will become significant T-bill buyers. The theory is elegant: stablecoins, like banks in the 1950s, cannot pay interest directly to stablecoin holders/depositors. However, stablecoin account holders can receive reduced crypto platform fees as a form of quasi-interest (in banking, this is referred to as earnings credit rate rather than paying interest on deposits). In the 1950s banks gave depositors toasters and other “gifts” while depositors earned no interest and Treasuries totaled 40-50% of US banks’ assets.

The Administration wants to keep the maturity of the Treasury market short to reduce borrowing costs, and stablecoin is seen as “creating demand” for T-bills. There’s expected to be foreign demand for USD stablecoins because blockchains are not an official payment system (so perhaps perceived as lower sanction risk), there’s no need for a bank account to hold USD, and they’re accessible anywhere.

But stablecoins depend on crypto – crypto rewards are stablecoins’ door prize to holders, and crypto faces significant challenges

· competition with AI for electricity,

· less use given diminished settlement of sanctioned oil from Venezuela and Iran,

· considerably higher volatility than stablecoins themselves.

You can see how growth in USD stablecoin market cap stalls out when Bitcoin prices decline meaningfully.

If crypto’s problems limit stablecoin growth, Treasury’s T-bill strategy faces a serious roadblock that would likely require Fed purchases.

So What’s a Bank Treasurer To Do in This Environment?

First, stress test your institution against a US inflation reacceleration scenario. Don’t just model one or two rate hikes. Model a scenario where the Fed needs to raise rates 200 basis points in late 2026 or 2027 to combat inflation that re-accelerates. How does your securities portfolio perform? What happens to your deposit base? Where are your vulnerabilities?

Second, review your credit underwriting. The loans you’re making today could be tested if the economy turns due to an AI productivity disappointment/Fed behind the curve scenario, and that turn could come quickly. The worst loans are made just before the economy turns south—don’t let that be your institution’s epitaph. Pay particular attention to:

-

Commercial real estate, especially office properties affected by work-from-home trends

-

Highly leveraged borrowers counting on refinancing at favorable rates that may not materialize

-

Private credit exposures, direct or indirect

-

Any lending tied to AI/tech sector assumptions about continued growth and cash generation

Third, maintain liquidity buffers above regulatory minimums. Yes, liquidity is expensive in terms of foregone yield. But we’ve seen three times in the past six years how quickly liquidity stress can materialize. The unrealized losses on your securities book are an anchor that limits your flexibility. Don’t compound that constraint by running thin on liquidity.

Fourth, prepare for volatility in Treasury markets. The structural supply-demand imbalance in Treasuries isn’t going away. Foreign buyers are pulling back. Term premia are rising. The distinction between fiscal and monetary policy is blurring. These are conditions that breed volatility. Make sure your ALCO, risk management systems and governance processes can handle significant Treasury market dislocations.

Alternative Scenarios

There are scenarios where things work out well.

· AI actually delivers high productivity growth on a much faster timeline than I expect

-

Stablecoins successfully help finance the U.S. government cheaply

-

Tariff and trade disputes are resolved, reducing inflation risks

-

OBBBA stimulus is delivered without a pickup in inflation because US consumers decide to save their refunds.

These outcomes also are possible, but they are not my baseline. I don’t think the market is appropriately pricing the alternative scenarios where:

-

Inflation re-accelerates by mid-to-late 2026, causing a shift in Fed policy expectations

-

AI productivity gains remain elusive in the near term while cap-ex pressures continue

-

The Fed finds itself behind the curve by early 2027

-

AI stocks get repriced to reflect the cap-ex heavy, lower free cash flow businesses they’ve become

-

The fiscal situation deteriorates further and Treasury market functioning is impaired by structural supply-demand imbalances

There are even darker scenarios—war with Iran, Japanese retail investor repatriation out of AI stocks, sharp decline in the US dollar —but I’m focused on the base case risks that aren’t being priced.

The Dot.com Movie That Should Be Made

So why hasn’t Hollywood made a movie about the dot.com period? Maybe it’s because tech is hard and the real story is too nuanced. The dot.com bubble burst because valuations got too far ahead of fundamentals, because easy money encouraged excessive risk-taking, and because policymakers kept excess accommodation in place too long based on optimistic assumptions about technology-induced productivity that took longer to materialize than expected.

Sound familiar?

The lesson from the Dot.com era isn’t that technology booms always end badly. The internet did transform productivity and our economy just on a longer timeline than the 1999-2000 market valuations assumed. The lesson is about timing, about policy discipline, and about the danger of making current decisions based on future benefits that haven’t yet arrived.