December 2025 – Christmas Sequel: Home Alone II as the Fed and Treasury Stimulate, Leaving Affordability Behind

Christmas Sequel: Home Alone II as the Fed and Treasury Stimulate, Leaving Affordability Behind

The holidays are fast approaching, and I love to share movies with family. After the recent Fed meeting, I found myself reflecting on Home Alone II. Kevin McCallister wasn’t supposed to end up alone in New York—again. Yet in Home Alone II, a small mistake at the airport snowballs into another holiday disaster: the same characters, the same misplaced confidence, and the same avoidable consequences. Watching you can’t help but think: haven’t we seen this movie before? Of course, that is the point of a sequel.

That movie feels uncomfortably relevant to recent Federal Reserve and US economic policy more generally. By cutting interest rates with inflation still above target and fiscal stimulus on the horizon, the Fed appears to have replayed a 2024 script—one where labor market precaution keeps inflation above target. This is making long-dated yields rise and prompting the Administration to reassure on the future of Fed independence. At the same time, Fed officials moved to expand the Fed’s balance sheet, growing it just enough to seem like they are not asleep on the couch but not enough to relieve pressure in U.S. money markets before year-end. While these purchases are reserve management purchases (RMPs), as I will explain, they do carry a distinctly QE-like flavor through supporting Treasury shortening the WAM of government debt, blurring the line between liquidity operations and outright monetary accommodation.

As with Kevin’s New York adventure, the setting may be different, but the themes are familiar: misjudged risks, improvised fixes, and consequences that linger well beyond the holidays. In my last column of 2025, I will unpack what the Fed’s Dec decision means for markets and banks, talk a bit about the upcoming Federal Reserve leadership transition and end with key things banks should keep in mind on these topics as we head into 2026, including the upcoming Bank of Japan meeting.

1. December FOMC: Expect Inflation to remain above target and long-dated yields elevated

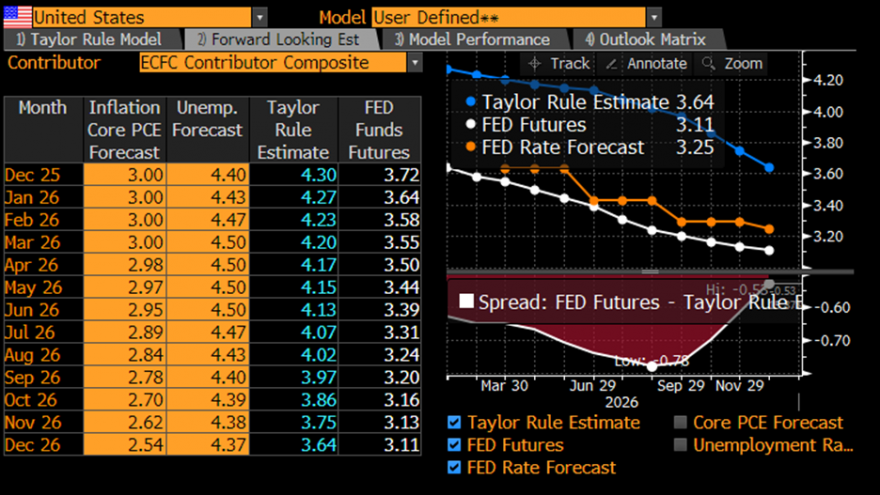

At the Dec FOMC meeting, the Federal Reserve voted 9 to 3 to lower the Fed funds rate by 25 bps to a range of 3.5% to 3.75%. A Taylor rule adjusted to what seems consistent with the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections for the “longer run” suggests that the Fed’s Dec rate cut was (again) not really a gift that the US economy needed.

It also was a surprising gift given the initial messaging after Oct FOMC and the relative paucity of US economic data due to the US government shutdown. There is a slew of data coming before Jan FOMC, including CPI data on Dec 18th. However, it seems another rate cut just couldn’t wait until 2026.

To cut even as inflation remains above target showed a continued Fed dovish bias as opposed to the “hawkish cut” that markets had been led to expect in Oct.

Chair Powell’s optimistic comments at the press conference about the path of inflation next year were truly notable in light of Christmas’ past, present and future –

· Inflation being above target for more than four and a half years and counting,

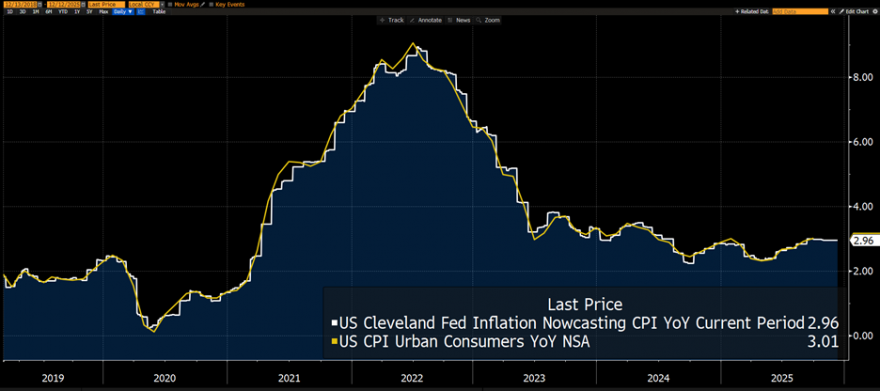

· The Cleveland Fed CPI Nowcast suggesting progress on getting back to target has stalled out (glad to see that one of the dissenters noticed),

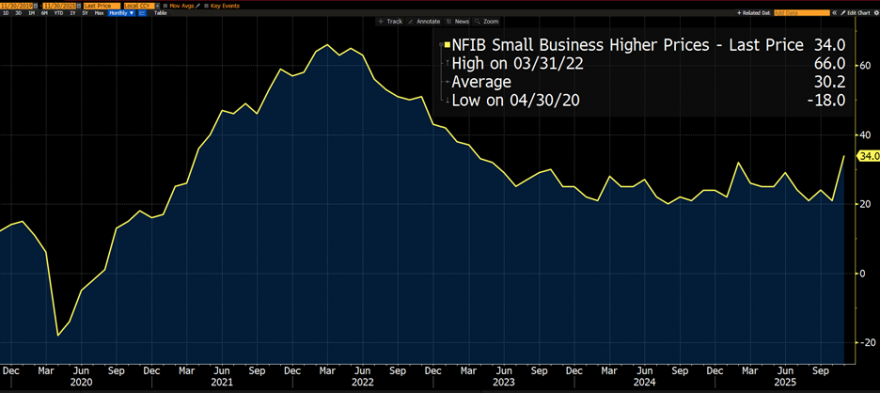

· NFIB’s most recent small business survey shows 34% of small US businesses raised prices in Nov, the highest level since Mar 2023 and the biggest increase in series history, and

· OBBA tax refunds and fiscal stimulus are on the horizon in 2026 with a tight labor market due to immigration policy (a key difference relative to 2024). At the same time, some policymakers appear overfocused on potential AI-related disinflation despite AI still being deep in the resource intensive cap-ex built out phase.

Some readers might push back and note that market implied measures of inflation expectations have come down notably.

However, trading in inflation derivatives, as noted by Treasury’s Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC), has become polluted due to the failure to publish CPI timely in Q4 due to the government shutdown. To quote TBAC’s November report to the Treasury Secretary:

The delay, or in some cases absence, of data is raising focus on the calculation methodology for TIPS and CPI Inflation swaps, in the absence of CPI. Treasury’s approach for CPI-related index contingencies is clearly stated in the Uniform Offering Circular. The Committee highlighted industry focus on the potential implications for the inflation swaps market if multiple CPI prints are missed, which could affect both demand for and secondary market liquidity in TIPS.

At the same time, US real GDP growth is strong. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow measure suggests US Q4 real GDP growth is likely to clock in above 3.5% q/q versus estimates of 2.9% q/q in Q3.

Extending a trend from last year, more wanna-be FOMC dissenters – particularly among Reserve Banks — signaled their discomfort with further Fed rate cuts in 2026 through their forecasts in the Dec Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) – six FOMC members submitted SEP forecasts that suggested a preference not to have cut rates at this meeting. But eight Reserve Banks did not request a cut to the discount rate at this meeting. Friends – if you want to make a point, then just dissent. Remember the Nike slogan – Just Do It! By contrast, last holiday season only four FOMC officials disagreed via the Dec 2024 SEP with the FOMC’s Dec 2024 rate cut.

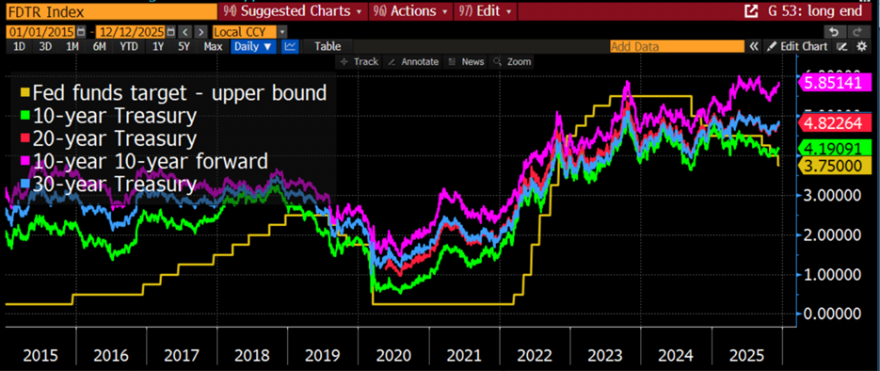

Long-dated Treasuries and, by extension, long-dated forward rates continue to not respond well to Fed rate cuts. This negative price action is even more notable despite the Treasury Dept increasing its use of buybacks and also shortening the weighted average maturity (WAM) of the Treasury market. You can read my recent pre-Dec FOMC interview on the Treasury market with Valor, a Brazilian financial newspaper Valor, here.

2. Long-dated yields rise again

This price action is becoming an ever-stronger bond market hint that Fed and Treasury colleagues would do well to pay more attention to – specifically, that an inflation/overheating policy error is at risk of unfolding next year.

The 10-year 10-year forward Treasury rate does not seem to be taking much note of Fed rate cuts. The dollar also weakened about 1% after Dec FOMC.

3. Don’t scare the children: time to reassure on the future of Fed leadership

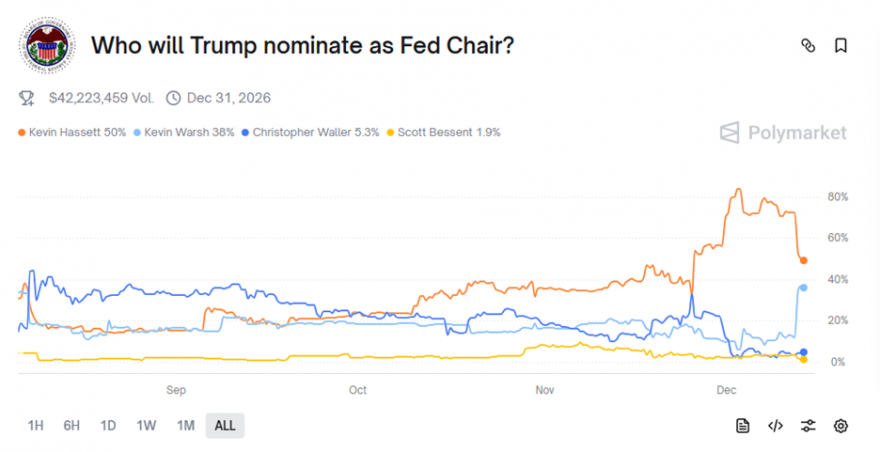

Perhaps for this reason, the Administration is trying to address rising long-dated Treasury yields by reassuring the bond market on upcoming Fed leadership changes. The odds in online betting markets seem to have shifted notably on the Fed Chair after Kevin Warsh’s meeting last week with President Trump.

Afterwards, Jamie Dimon even weighed in favorably on Kevin Warsh relative to Kevin Hassett – though I said it first! It does seem like the next Fed chair may be decided based on financial market reaction and financial sector feedback.

It also was hard to miss that all 12 of the Reserve Bank presidents were unanimously reappointed shortly after the Dec FOMC meeting in a vote that included Trump-appointed Fed Governor Miran. It was reassuring to see outspoken Fed Presidents not be targeted for removal.

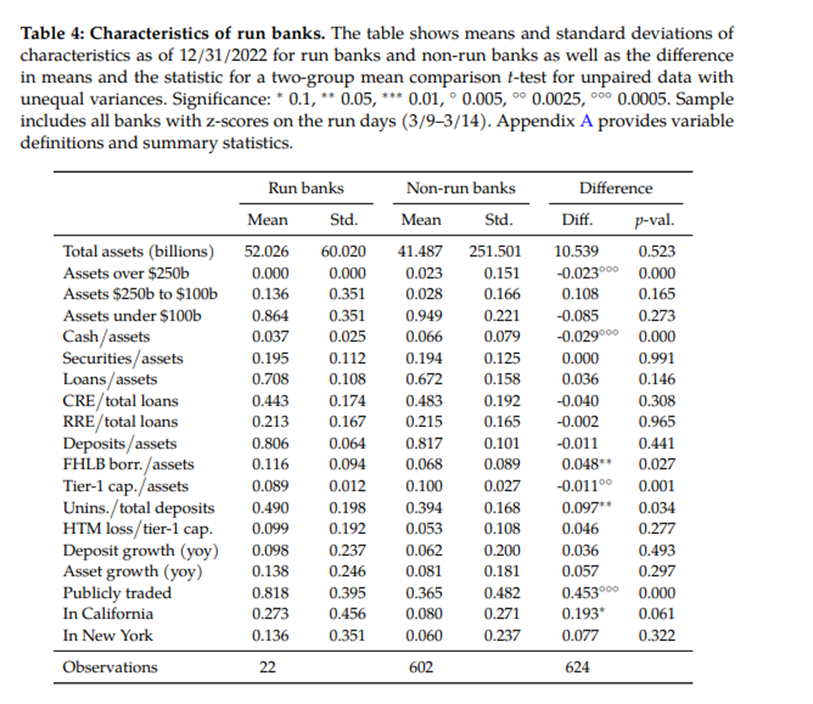

However, it does seem that being dovish helped spur collective amnesia about SF Fed President Daly’s 2023 supervisory and discount window failures. While expunged from the current version of a recent Fed paper that analyzes bank runs around the time of SVB’s failure, an earlier version of the paper included this table which suggests that banks in CA were more likely to have experienced runs in 2023. One could easily have tested whether there was a specific loss of confidence in Fed chartered banks overseen by SF – but that analysis is not fit to print. And only Fed staff have access to the Fedwire data used in the paper to assess the scope of runs in the banking sector in the spring of 2023.

Having been a banking market participant at the time when SVB failed, I can vouch that there was a palpable loss of confidence in FRB-SF supervision and discount window lending. However, it seems Reserve Bank presidents remain both independent and, depending on your monetary policy views, unaccountable for meaningful failures at their Reserve Banks. It shows a lack of meaningful change at the Fed with regards to accountability and is unfortunate.

Time will tell whether these steps from the Administration to sooth the bond market on Fed leadership are sufficient to settle long-dated Treasury yields or not.

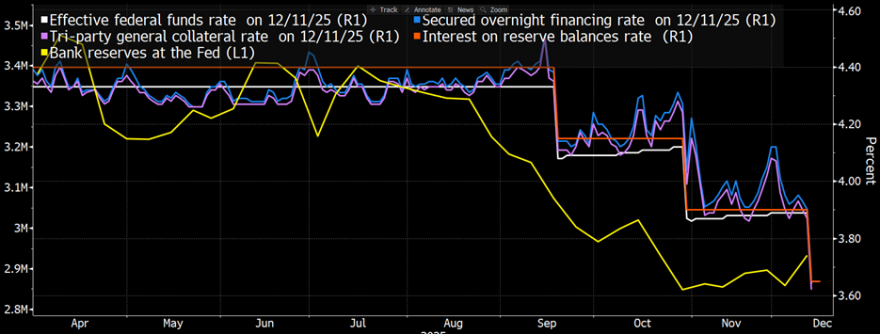

4. Reserves not ample; RMPs help, but aren’t large enough; expect either larger RMPs or money market volatility to continue for several months.

Turning to the Fed’s balance sheet, at the December meeting, Chair Powell still declared banking system reserves “ample” even as the FOMC approved a very rushed transition from an end of QT to resumed Fed balance sheet growth. Honestly, I was pleasantly surprised that change is possible.

The Fed began RMPs effective on Friday Dec 12th. Under RMPs, the Fed will buy nominal and inflation adjusted Treasury securities with a residual maturity of up to 3- years.

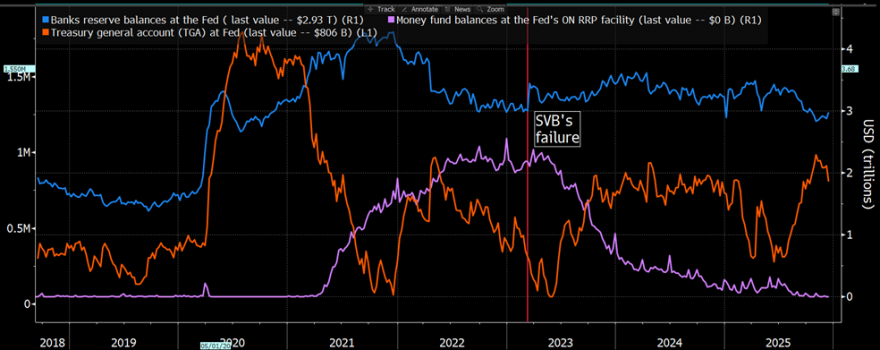

Reserve balances at US banks currently stand at ~$2.93 trillion. As regular readers of this column know, I have long maintained that allowing reserve balances in the US banking sector to fall below the $3 trillion level where SVB failed in March 2023 would cause bank funding and money market issues.

This proved to be the case as money market conditions were becoming more disorderly as reserve balances declined below $3 trillion. It is senseless for the FOMC to approve cuts to administered rates while tightening liquidity in the financial system. This week’s decision sought to reduce that paradox/contradiction.

However, while $40 billion per month growth in reserve balances is helpful – it is still inadequate to deal with near term liquidity problems like year-end. Money markets do not respond to forward guidance on the balance sheet. Bluntly, there is either sufficient liquidity in the US financial system or there is not. As a result, I anticipate that US money markets will see upward pressure on rates around year end despite the Dec RMP announcement.

Also, the Fed controls only the size of its balance sheet – not the composition of its liabilities which are 1) reserves at banks, 2) money fund balances at the Fed’s ON RRP facility and 3) Treasury’s account at the Fed (TGA).

Indeed, growth in the TGA due to April tax season will drain bank reserves in early 2026. It is plausible at the $40 per month pace it will take several months to restore reserve abundance. Additionally, Treasury shortening its WAM implies a higher Treasury cash balance at the Fed – which drains bank reserves at the Fed. Finally, any kind of upward repricing of Fed rate expectations in 2026 could see money fund balances move out of T-bills and into the Fed’s ON RRP which would drain reserves from banks.

All of this suggests that while RMPs help improve bank and financial sector liquidity – the currently announced RMP sizes are likely too small and fail to consider potential pressures from unexpected growth in other Fed liabilities. Therefore, it is plausible to anticipate that either RMP sizes may need to increase or meaningful money market rate volatility on certain days will continue to ensue.

So, it is likely that the Fed’s RMP actions still are not enough. US banking system reserves are no longer abundant, and the standing repo facility (SRF) is insufficient as a tool. Reserves at the Fed are of course a bank asset; the SRF or discount window borrowings are, by contrast, bank liabilities. Also there is the problem of stigma and only ~40 banks are signed up for SRF.

5. Are RMPs QE? Yes, sort of — but not by the Fed directly.

The Fed intends its purchases to ensure bank reserves are ample. However, RMPs will assist the Treasury in shortening the WAM, financing the 2026 deficit expansion and funding Treasury buybacks which target the long-end. So indirectly, RMPs do help finance Treasury, including Treasury buybacks which are a type of Treasury-led QE. However, unlike Fed QE, RMPs and Treasury buybacks have no obvious forward guidance effects on long-term US rates.

The Fed’s purpose of its Treasury purchases is to ensure an ample supply of US bank reserves and, yes, the Fed is only buying T-bills and, when needed, securities with a residual maturity of 3 years or less.

Stated very simply, the Fed’s actions are needed to ensure ample reserves at banks. Yet, these RMPs will also assist Treasury re: front-end demand to permit the Treasury to shorten the WAM and conduct buybacks. Treasury buybacks at the long-end total about 15-20% of supply. Think of it as Treasury-led QE, but financed via the Fed at the front end.

It Is not a stretch to say that debt management changes to Treasury market WAM share some features of QE. QE affects the volume and the maturity of bonds the market is induced to hold, and so might influence the shape of the yield curve. The decisions of government debt managers on WAM and buybacks have very similar effects.

BIS researchers raised the potential for debt managers to act in a manner akin to unconventional monetary policy over a decade ago. The authors found that lowering the WAM of US Treasury debt held outside the Federal Reserve by one year is estimated to reduce the five-year forward 10-year Treasury yield by 130-150 bps. They also attribute the decline in long-term Treasury yields between 2001- and 2005 which at the time Alan Greenspan dubbed a “conundrum” to a decline in the WAM of the Treasury market from 70 to 56 months.

Writing in 2013, the BIS researchers cautioned against extrapolating their results on shortening the WAM to implications for long-term interest rates stating that

given that public debt has grown to very high levels, fiscal policy may well be conducted differently than during the sample period. Different expected [fiscal] consolidation paths may mean that the same change in debt maturity could have a different impact on long-term rates. In addition, inflation expectations could be destabilized by radical change in debt management policy.

So, RMPs are not Fed-led QE, but are an enabler of Treasury shortening the WAM which share some features of QE.

6. Why did this mistaken situation of reserve scarcity happen again at the Fed?

Two reasons in my view.

First, the Fed’s operating losses due to interest rate risk are among the highest of all G-7 central banks. If Fed QT was ended “too soon” and the Fed funds rate was still high, the Fed’s balance sheet would have grown involuntarily due to ongoing interest rate losses. Recall in Chair Powell’s October NABE speech on the Fed’s balance sheet, he said

While our net interest income has temporarily been negative due to the rapid rise in policy rates to control inflation, this is highly unusual. Our net income will soon turn positive again, as it typically has been throughout our history. Of course, having negative net income has no bearing on our ability to conduct monetary policy or meet our financial obligations.

Powell’s statement suggests that the P&L of the Fed may have had some bearing of their thinking about balance sheet timing in conjunction with the actions on the Fed funds rate. I suspect that Fed losses mattered to end of QT timing. Fed losses do have fiscal implications as they are a big loss of seigniorage paid to the Treasury. Involuntary growth in the Fed’s balance sheet due to ending QT while losses were accruing also would have been awkward in communicating monetary policy to the public.

Second, Treasury Secretary Bessent and others in the Administration have been highly critical of the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. This created political pressure on the Fed to shrink its balance sheet as much as possible. To be clear, I agree with most of what the Administration has said about the problems of a large Fed balance sheet. However, one can have the right problem statement, but the wrong solution.

Specifically, what I do not agree with is that policymakers can somehow painlessly or seamlessly shrink the Fed’s balance sheet back to pre-COVID levels. The reason for that is that we have created an environment for years of abundant liquidity in the US banking sector. The Fed is not the first central bank to shrink its balance sheet, but the US has experienced more problems that other countries – why?

7. Why can’t the Fed seem to shrink its balance sheet back to pre-Covid levels?

The answer is that we lack effective regulation and supervision of both liquidity and interest rate risk in the US banking sector. So when you don’t have good regulatory and supervisory controls around liquidity and interest rate risk and the central bank shifts liquidity conditions sharply, there can be problems at banks and, in turn, markets.

After the spring 2023 bank failures, no changes were made to strengthen quantitative regulation of liquidity and interest rate risk at US banks. Some banks with significant unrealized losses on securities and fixed rate mortgages still have not meaningfully strengthened capital. That is a failure of the Biden Administration. Efforts to further deregulate liquidity and interest rate risk – including diluting the LCR and abolishing supervisory model risk management expectations — if enacted – would be a failure of this Administration or Congress. Supervisory weaknesses come at the cost of difficulty in winding down the size of the Fed’s balance sheet.

The record levels of margin debt, leverage in crypto and bank liquidity provision to NDFIs all are signs of the financial stability risks arising from abundant liquidity provision. Central bank liquidity is an enabler — but my view is that one would be playing with fire to try to shoehorn the Fed’s balance sheet back to pre-Covid levels given the absence of meaningful regulation and supervision of liquidity and interest rate risk at banks.

8. Bank of Japan meeting final major risk event in 2025

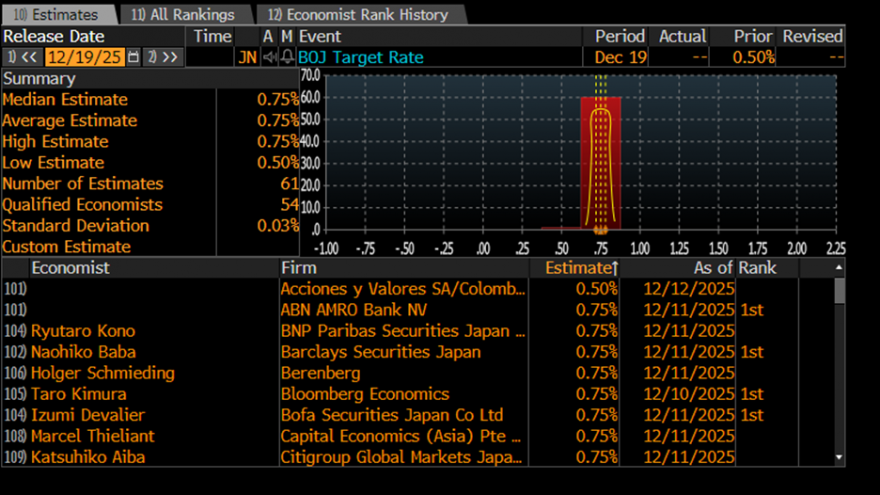

From a North American perspective, it is tempting after the Fed meeting to call 2025 over and focus in on family and friends. However, the Bank of Japan will conduct its final meeting of the year on Dec 19th. The strong consensus is that BOJ will (finally!) raise its policy rate by 25 bps to 0.75%.

This is important as Japan is one of the world’s largest exporters of capital and the #1 beneficiary of those capital flows is the U.S. Japan has struggled with the inter-related problem of above target inflation and a weak yen since Covid and headline inflation in Japan remains at 3%.

A dovish Fed meeting and end of year holidays is the perfect time for the BOJ to try to make progress in reversing yen weakness and help bring energy and food import-related inflation down.

Japan and its banks so far seem well-prepared for higher interest rates and a steeper JGB curve.

But higher Japanese interest rates do pose risks to a reversal of capital flows from Japan which could tighten financial conditions abroad and, most notably, in the US. Could it act as a further source of upward pressure on long-dated Treasury yields? My view is yes.

9. In closing, what does this Home Alone II sequel mean for banks in the months ahead?

· The BOJ rate decision shortly before Christmas is the final key risk event of 2025 that could exacerbate rising long-dated yields and tighten financial conditions. You can read more about the structural risks to a reversal of the yen carry trade here.

· While the recently announced RMPs are helpful, their size is likely inadequate in the near term and US money market volatility should be expected to continue into year end and Q1. So, mind your liquidity and interest rate risk even if bank regulators are not asking you to.

· US policymakers may have forgotten affordability again. My basecase is limited progress on inflation coming back to target is made in 2026 and results in higher long-term US interest rates.

· The current Fed policy path is priced dovish relative to what a forward Taylor would suggest given consensus private sector economic forecasts.

· Don’t be complacent and consider potential shocks to long-term US interest rates in your 2026 stress tests. The Administration is looking to reassure on the future of Fed leadership – will it be enough to calm long-dated yields? I think these actions are helpful, but the fiscal policy path and bringing the primary budget deficit down is likely more important.

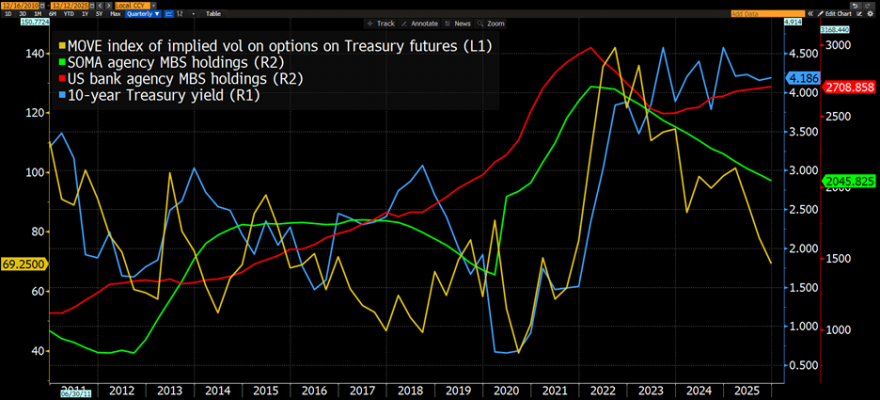

· Having real debate among policymakers is valuable and important – particularly given the meaningful Fed policy errors since Covid. However, growing divergence in policy views on the FOMC should increase interest rate (and asset price) volatility, all else equal. Data show that US banks are buying more agency MBS even as the Fed is allowing agency MBS to run off its balance sheet. Banks already are short interest rate volatility by virtue of being mostly deposit-funded. For this reason, careful scenario analysis of agency MBS purchases is merited.

· Absent substantial progress on the budget deficit, higher long-dated Treasury yields could result in a return to “real” Fed QE is plausible in 2026. Additionally, the Administration may prefer to make a return to QE a decision for current Fed leadership to own.

Summing up:

2025 has been a volatile year.

As the year comes to a close, I am grateful for the opportunity to share reflections with Bank Treasury Talk readers.

As we head into 2026, a resilient outlook, thoughtful assessment and high level of preparedness are all helpful.

I will be speaking at the CeFPro Treasury & ALM conference in March 2026 in NYC . You can register here Event Homepage – Treasury & ALM USA

I also will be in Mexico City at an event hosted by GARP in March 2026. I look forward to seeing some BTRM, Treasury Talk readers and banking friends at both of these events.

Also, soon we will share some information about several BTRM banking thought leadership webinars in Q1 2026 that I will host.

I sincerely wish you all a healthy and happy holiday season surrounded by both family and friends!