September 2025 – Markets prefer the blue pill, but watch out for an inflation revival and associated rate repricing; stablecoins a risk to bank deposits

In my 2025 Treasury Talk columns, movies have served as a helpful hook to convey key themes. In August, I wrote about the movie “Groundhog Day” and argued that we should expect to see some time loops — Team Transitory 2.0 on inflation, liquidity conditions becoming more challenged for banks and growing likelihood of an eventual shift in the posture of the Fed’s balance sheet. So far, I consider myself two for three from August.

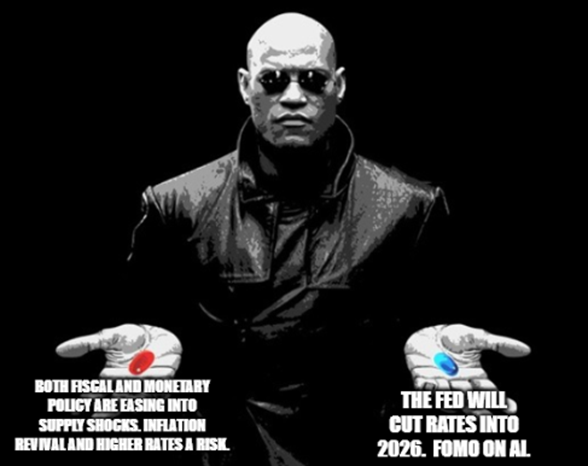

The movie hook of my September column is The Matrix — a sci-fi movie about choice. Matrix fans recall the film’s iconic red pill/blue pill scene. Morpheus explains to the movie’s hero, Neo, that many people would prefer illusion when reality challenges existing beliefs and comfort. Morpheus emphasizes to Neo that accepting the truth/reality requires knowledge and courage. Morpheus then asks Neo if he would prefer the blue pill/illusion or the red pill/reality.

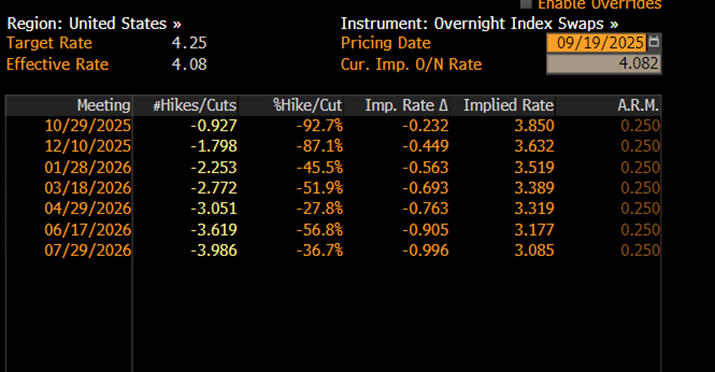

After the Sept FOMC meeting and 25 bps rate cut, it would seem many prefer the blue pill – believing in more Fed rate cuts (and, relatedly, in US asset markets rallying further). Further Fed rate cuts in Q4 and into early 2026, are currently priced in.

The market’s blue pill preference for Fed rate cuts is understandable – bonuses are set soon!

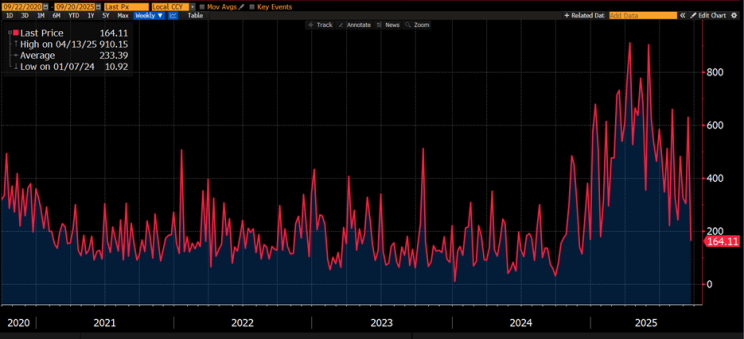

But while the US economy was hit with significant shocks related to tariffs and immigration/labor force earlier this year, the corporate sector is trying to adjust. Although still elevated relative to 2024, US economic policy uncertainty (red line) is basically at year-to-date lows. US companies are trying to work through trade and immigration policy shifts. Up until now, US corporations have absorbed these negative supply shocks. Yes, I did read the news about the Administration’s executive order imposing a $100,000 HB-1 visa program fee on Friday, but this announcement affects a narrow range of companies and also will be subject to legal challenge.

I am more focused on the point that with more open wallets around holiday season and stimulative fiscal policy arriving soon, the scene is set for higher costs to be passed on to consumers and US inflation to rise further above target. Specifically, as explained in August, Q1 2026 tax refunds will be large due to lack of IRS OBBBA tax table guidance– which is the point headed into the US mid-term elections. Fiscal stimulus may afford US companies the opportunity to pass along more costs associated with these negative supply shocks to consumers, elevating US inflation further in late 2025 and early 2026. Also, if the economy strengthens due to fiscal stimulus, labor demand may pick up even as labor supply remains subdued due to changes in immigration policy and aging demographics.

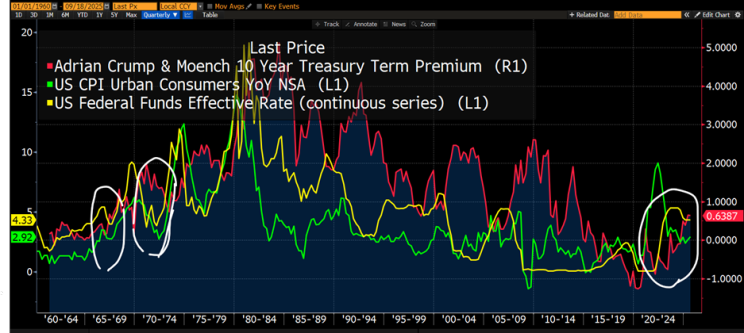

In my first column in Sept 2024, I disagreed with contemporaneously easing fiscal and monetary policy and the 50 bps Sept 2024 rate cut before US inflation had returned to target. The 10-year Treasury yield rose almost 100 bps during the Fed’s 100 bps Q4 2024 rate cuts.

As I suggested in my August column, I still disagree with cutting rates and easing fiscal simultaneously — different Administration/mostly same FOMC. The Sept 2025 US economic update from Congressional Budget Office (CBO) includes CBO revising up its forecasts for US economic growth and inflation and revising down its forecast for unemployment in 2026 in light of fiscal policy changes. CBO also states that

policy changes … led CBO to increase its projection of economic growth in 2025 and 2026. Households’ higher after-tax income, more favorable tax treatment of investment for businesses and increased federal spending on defense, border security and immigration increase overall demand for goods and services. That increased aggregate demand creates inflationary pressure, prompting the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates more slowly than it would otherwise.

During new Fed Governor Miran’s Senate confirmation hearing last week, he reminded that “Congress wisely tasked the Fed with pursuing price stability, maximum employment and moderate long-term interest rates” (emphasis added). Over this weekend (9/20-21), the idea has reemerged of Treasury Secretary Bessent running both the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department. The lines between the Fed and Treasury have become blurred as a result of unconventional monetary policy. So yet another Fed mandate seems to have emerged — reducing government interest expense/stabilizing the Treasury market. No, the balance among the Fed’s mandates does not seem symmetric. And too many conflicting mandates makes it difficult for the Fed to achieve any of its statutory objectives.

To be fair to the entire FOMC, Fed Chair Powell’s dovish comments in August at the Fed’s annual Jackson Hole meeting effectively pre-committed the Committee to a Sept rate cut. It was evident that there were divergent views even at the time of Jackson Hole (see Cleveland Fed President Beth Hammack’s CNBC interview – well done!). But, given Governor Miran joined the FOMC while still a member of the White House staff and the legal challenges facing Federal Reserve Governor Cook, it appears that the rest of the FOMC decided to support Chair Powell at this meeting with a 25 bps rate cut (ex-Miran who voted for a 50 bps rate cut). Take note that Governor Miran will explain his views in a speech on Monday (9/22), eschewing Fed practice of dissenting FOMC voters writing a short statement.

A Fed-Chair driven highly consensual approach is the typical Fed policymaking. But it really did not square at all with the FOMC’s Sept Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) release which showed highly divergent perspectives on both the US economy and the Fed policy outlook. Unfortunately, the homogeneity in voting at the Sept FOMC arguably didn’t help the Fed’s case on the importance of an independent-thinking central bank.

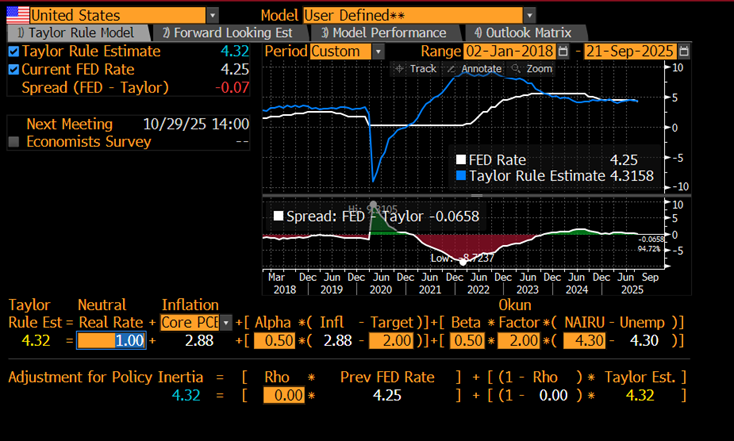

Big picture, the case for the Sept 2025 rate cut was weak; the case for further Fed rate cuts appears weaker still. Specifically,

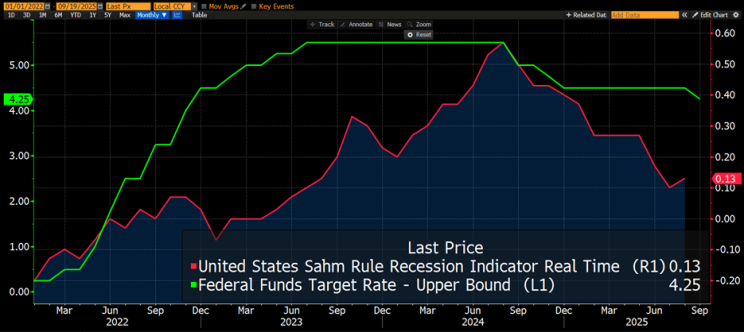

1. the Sahm rule, an indicator of labor market recession risks, is nowhere close to being triggered,

2. real time estimates of US GDP growth suggest the economy is accelerating,

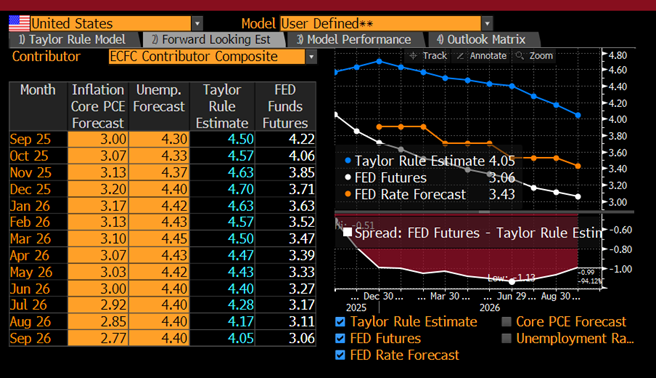

3. the Taylor rule does not suggest further Fed rate cuts are needed (first exhibit) or on a prospective basis in light of Bloomberg consensus private sector forecasts for inflation and unemployment (second exhibit),

4. recent developments in realized inflation (above target and rising) and what inflation derivatives tell us about sophisticated investors’ US inflation outlook over the next year (expected inflation stays above target) also don’t point towards Fed rate cuts,

5. on a long-run basis, US financial conditions already are relatively easy/accommodative.

To be fair, the Fed is in a difficult situation. The Administration is: 1) pushing the Fed very hard to cut interest rates, 2) regularly criticizing the Fed and 3) actively seeking ways to replace senior Fed leadership.[1] The Administration’s comments can shape US interest rate expectations, which can create an uncomfortable gap between market expectations of the Fed’s policy path and what the Fed actually may need to do to bring US inflation back to target. If the US were to get to 3.5% or 4% inflation in H1 2026 and the Fed failed to respond or even continued to cut interest rates, it is unlikely such a scenario would be constructive for confidence in the US economy and US markets, most notably the dollar. Also, this Administration – like the last Administration — continues to fund the US government with a higher reliance on short-term T-bills and has not refilled the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR), both of which increase the risks to the US economy of associated with an inflation shock.[2]

So, to sum up, banks should not get overly sanguine on lower US interest rates. Specifically, it is plausible that either

- there may be too many rate cuts currently priced in given fiscal stimulus on the horizon; or

- if the Fed cuts despite coming fiscal stimulus the 10-year Treasury term premium may rise further (see 1965 and early 1970s). While 10-year Treasury term premium bottomed during Covid and trended higher (red line), its current level is still less than half its long-run average.

On stablecoin, I have been fielding a lot of questions about stablecoin from friends in financial services. Stablecoins do seem run prone and yes, stablecoins will likely create risks for US banks’ $6 trillion in non-interest-bearing deposits. So I wanted to share links to a recent podcast I did with Hedge Fund Research here and re-recording of a keynote lecture here I gave on money transmission and banking at a large national conference in KY in Sept that placed USD stablecoin and the new US cross-border remittance tax in a broader macro and banking context. These discussions may be a good listen on a walk, at the gym or during a commute.

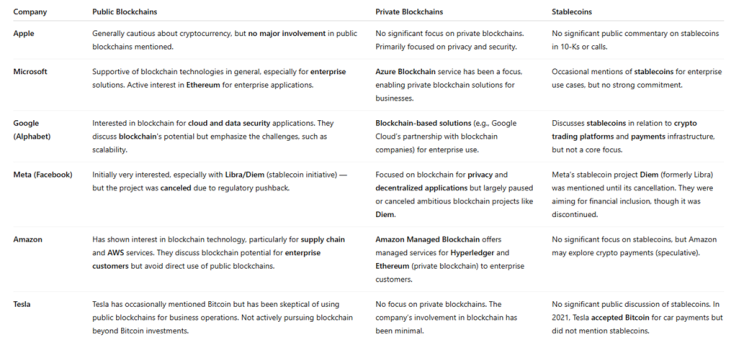

Per ChatGPT, here’s a summary of what the most recent 10-K reports and earnings calls reveal about biggest US tech firms’ engagement/adoption of public blockchains, private blockchains and stablecoins. Oh, wait –hmm… no rush to adopt in evidence here. But, I am sure that these guys are slow on technology. 😊

I wish all Treasury Talk readers a strong start to Q4 — don’t get overly directional on US interest rates (I do hope that I am wrong on balance of risks/inflation), keep focused on deposits as stablecoins move forward and Fed QT continues; and please don’t give up on your quarterly earnings releases!

[1] While I do agree with a number of Secretary Treasury Bessent’s recent op-ed critiques of the Fed – particularly unconventional monetary policy and supervision — Congress is ultimately responsible for decades of overly expansive fiscal policy and, per CBO analysis, the 2025 OBBBA transfers more resources both on an absolute basis and a percentage of income to higher income and older households, increasing US income inequality.

[2] Some may think “optimal US Treasury debt” should have a lower weighted average maturity (WAM). But a lower Treasury WAM implies both greater interest variability and rollover risk. Higher levels of economic policy uncertainty, still above target US inflation and greater risks of external shocks like war, pandemics and cyber threats suggest a lower Treasury WAM may feel smart until quite suddenly it is not.