June 2025 – Say what? Let’s lower US bank capital to reduce Treasury market fragility while Fed QT continues?

My sincere apologies to Treasury Talk Readers for missing a column in May. May was terrific, but also a bit of a blur. I spoke at two banking conferences in Miami and testified on Treasury market fragilities and the US financial sector in the US House Financial Services Committee. Video of the Congressional hearing can be found here. In the Hill testimony, I took a question about the idea of the Fed not paying banks interest on reserves. This is a tax on banks and another example of how unconventional monetary policy can be detrimental to bank health. You can watch the video — but bank treasury teams should study a “no interest on reserves” as a “what if.” This idea, which has been implemented in other countries, seems to have garnered some US followers.

While June FOMC is next week, I think the Fed waits for more data to judge the impact of tariffs, tax legislation and economic policy uncertainty on the economy until September. So, the June Treasury Talk column instead focuses readers on two related paradoxes:

- Future proposed changes to reduce US bank capital requirements to allow banks to “hold more Treasuries” even as stagflation and recession probabilities are elevated; and

- Continued Federal Reserve quantitative tightening (QT) amidst handwringing about “Treasury market fragility” so lowering bank capital is a “must do” item.

Changes to US bank regulatory capital standards to “reduce Treasury market fragility” while 1) Fed balance sheet shrinkage is ongoing, 2) the government budget deficit is expanding and the 3) US current account deficit is narrowing are unlikely to prove effective. Instead, lower levels of US bank capital and concerns about the efficacy of US regulation and supervision in the context of rising US macroeconomic risks may erode US banks’ preeminent position among global investors in banks.

A range of less than Capitol ideas about bank capital

- Since the pandemic, US officials of both political parties have been attracted to proposals to remove Treasuries from large US banks’ supplementary leverage ratios (SLRs) even as both parties continue to run ever larger government budget deficits relative to GDP. [1] These calls to reduce non-risk based bank capital appear rooted in the idea of addressing “Treasury market fragilities” through financial regulation as opposed to more sound fiscal policy.

- Some in the US banking lobby are also advocating for changes to the risk-based capital surcharge for the most systemic US banks, or G-SIB surcharge, stating that it also is acting as a “unnecessary brake” on US banks’ intermediation of Treasuries.

- Finally, there also is advocacy from some on the Hill that the Tier 1 leverage ratio, which is a non-risk-based regulatory capital requirement that impacts all US banks, be reexamined, claiming that it constrains US bank investments in Treasury securities.

- In June the FDIC submitted a public notice that it had filed a proposed modification to SLR requirements to the White House Office of Management and Budget for review, suggesting that a proposed revision on the SLR is coming.

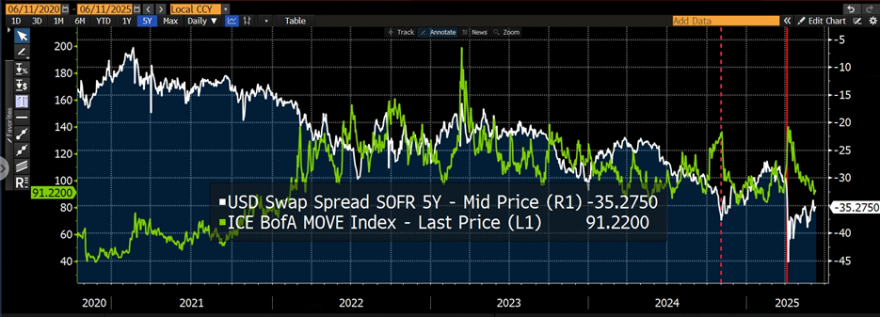

Since the November 2024 election (dotted red line), a number of hedge funds have traded the swap-cash basis trade on the notion that prospective changes in US bank leverage ratios imply that banks will buy more Treasuries and the spread between SOFR swaps and comparable maturity Treasuries would rise. The partial liquidation of this popular trade was a factor in April “liberation day” (solid red line) Treasury market volatility.

Stagflationary and even recession storm clouds on the horizon is the wrong time to discard the umbrella that more capital provides US banks. Banks are levered plays on the real economy and require more capital, not less, when the macro outlook is highly uncertain.

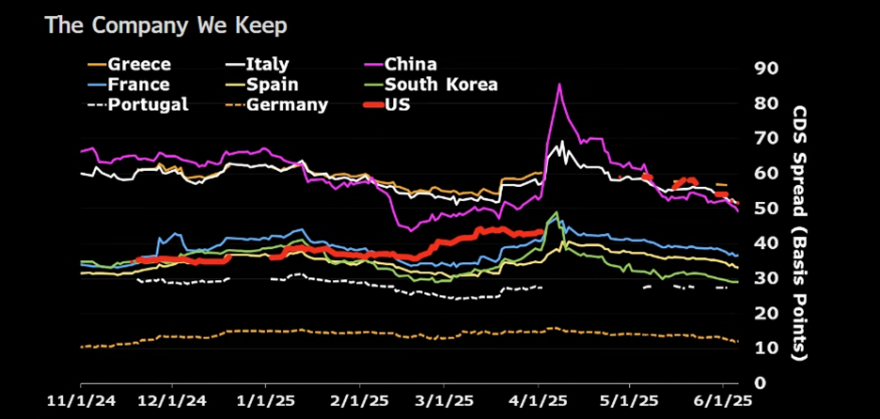

Financial regulation needs to be consistent in promoting sound risk management. Eliminating bank capital requirements for Treasuries when they exhibit heightened price volatility and when Treasuries may enter a long-term bear steepening due to structural factors (no more Cold War peace dividend, deglobalization, aging demographics, reduced immigration) is inconsistent with sound bank risk management. The Bloomberg chart below from highlights market perceptions of rising US sovereign risks.

And yet the eSLR isn’t binding on most US G-SIBs…

| US G-SIB Regulatory Capital Headroom in USD billions; Q1 2025 denotes most binding regulatory capital metric | ||||||||

| US G-SIB | Total capital adv | Total capital std | Tier 1 RBC adv | Tier 1 RBC std | CET1 adv | CET 1 std | Tier 1 lev | e-SLR |

| BAC | 41.6 | 13.5 | 47.6 | 12.9 | 49.8 | 18.1 | 90.8 | 28.7 |

| BNYM | 6.8 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 8.9 | 6.8 |

| Citi | 18.4 | 28.6 | 18.7 | 17.4 | 18.6 | 15.2 | 76.4 | 23.8 |

| GS | 38.4 | 12.5 | 41.3 | 12.2 | 36.5 | 7.8 | 48.7 | 9.8 |

| JPM | 46.7 | 43.8 | 65.3 | 48.7 | 72.9 | 56.5 | 131.9 | 51.5 |

| MS | 31.0 | 12.3 | 30.4 | 11.3 | 28.0 | 9.1 | 36.6 | 9.0 |

| STT | 6.7 | 5.0 | 7.1 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 4.1 |

| WFC | 47.7 | 23.0 | 47.5 | 15.8 | 45.2 | 15.8 | 78.2 | 40.5 |

Source: Company reports, Moody’s

However, the 2024 CCAR stress test results for the US G-SIBs paint a different story

| G-SIB | Projected minimum e-SLR under severely adverse scenario denotes below 5% |

| BAC | 4.8% |

| BNYM | 7.5% |

| Citi | 4.3% |

| GS | 3.5% |

| JPM | 5.2% |

| MS | 3.9% |

| STT | 6.0% |

| WFC | 5.2% |

Source: 2024 Federal Reserve stress test results

Specifically, the eSLR for half of US G-SIBs would decline below the required 5% e-SLR threshold under the severely adverse scenario of Federal Reserve’s 2024 CCAR stress test. The e-SLR is the only required regulatory capital ratio that some US G-SIBs cease to be compliant with under the stress test. This is because the US bank stress test largely evaluates a credit shock affecting large banks’ risk based capital. For years, the stress test has permitted US G-SIBs to eat into the 2% enhanced SLR buffer even though in practice falling below the 5% eSLR IRL would have adverse regulatory and potentially even market consequences. The CCAR stress testing methodology is being evaluated. It may also be wise to reconsider what it means to be a going concern. It is interesting to note that the CCAR results for US banks subject to the 3% SLR[2] indicate that these less systemic US banks remain comfortably above a 3% SLR and often have projected minimum SLRs in CCAR near e-SLR levels, i.e., north of 5%. The SLR picture for foreign banks’ US intermediate holding companies is more mixed.

Wasn’t the original purpose of supervisory stress testing to ensure banks have sufficient capital to continue lending to the real economy in a downturn while remaining well capitalized? It is important to review whether CCAR may have evolved into merely setting large US banks’ stress capital buffers, but arguably not accomplishing the macroprudential objective of ensuring a bank remains a going concern in the real world, i.e., well before breaching regulatory minimums.

So, yes, if a stress like a recession or credit downturn were to emerge in late 2025 or 2026, then the e-SLR could become binding on one or more US G-SIBs. But part of the reason for the e-SLR becoming binding is that the Federal Reserve’s stress test has downplayed the importance of G-SIB adherence to leverage standards in the stress test’s design and permitted dynamic assumptions on RWA over the stress test projection period that may ameliorate CET1 risks.

A recent blog from the US bank lobby cites The Group of Thirty report, “US Treasury Markets: Steps Toward Increased Resilience” in arguing for leverage ratio reform. The Group of Thirty report states that “[w]hen the SLR is binding or even when there is a significant chance that it will be binding in the future, banks are discouraged from allocation of capital to low-risk activities because the SLR requires too much capital to support those activities.”

Who are the authors of the Group of Thirty report? Mostly former central bankers who themselves failed to recognize that their overuse of unconventional monetary depressed the 10-year Treasury term premia and contributed to excessive government budget deficits. It is ok to make a mistake, but now they seem set to repeat it. They have now turned attention to advocating that the balance sheets of commercial banks also be signed up to the task of enabling even more expansionary fiscal policy.

Unfortunately, the history of financial regulation includes periods of financial repression. What is financial repression? It is when governments implement regulatory policies to channel funds to themselves. The US needs more domestic savings to fund the Treasury market if it narrows the current account deficit through tariffs and potentially also taxes foreign investments in the U.S.

Does financial repression sound farfetched? It is useful to remember how banks’ existing risk-based capital standards came into being. Following the Great Depression, US bank supervisors focused on banks’ capital to total asset ratio, effectively a leverage ratio. Following the end of World War II risk-based capital standards were developed and facilitated US banks’ substantial purchases of government securities which were granted a zero-risk weight, requiring no capital.

After World War II, US government debt to GDP was similar to current levels – roughly 100% of GDP. At the time, even though about 50% of US banking system assets were invested in US Treasuries, US banks’ holdings of Treasuries securities were actually not a source of financial instability. So why not encourage increased US banks’ holdings of Treasuries securities? Simply put, we are no longer in the financial system of the 1950s.

For instance, in the 1950s, Federal Reserve Regulation Q prohibited US banks from paying interest on checking accounts/demand deposits. In 1950, these deposits were about 75 percent of US banks’ total liabilities. That meant that 75 percent of US bank funding had zero interest cost. Ceilings also existed on the interest that US banks could pay on other deposit accounts. US banks were heavily invested in Treasuries and bank failures were negligible. In essence, Regulation Q permitted the US government to use banks to cheaply and safely fund the US government at negative real interest rates — the essence of financial repression. Given interest rate deregulation in the 1980s due to the growth of the US money market fund industry, today it is impossible to safely use US banks to fund the US government in such a manner again.

If anything, high bank exposure to Treasuries, combined with the continued absence of quantitative regulation of interest rate risk and weak supervision of interest rate risk, means that a sharp rise in Treasury yields can indeed pose a threat to US banks, as Silicon Valley Bank’s failure in 2023 revealed. Indeed, there have been no US regulatory changes post-SVB with regards to interest rate risk.[3] Clearly greater rigor on interest rate risk would be preferable but that isn’t coming – instead changes to bank capital related to Treasuries are on the table.

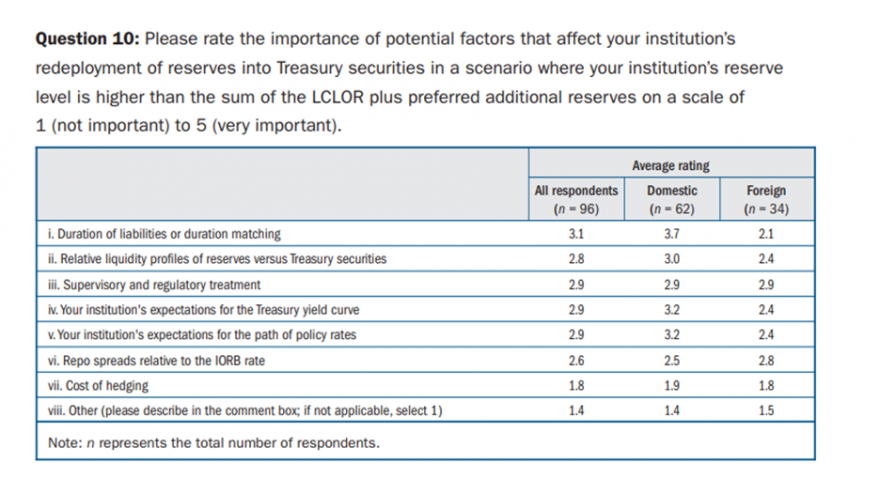

While regulatory capital treatment is a factor in US banks’ decision to hold Treasuries, Federal Reserve data also suggest it is far from being the most important one.

- Specifically, Federal Reserve’s Senior Financial Officer Survey (SFOS) suggests based on the March 2025 responses that domestic US banks view the regulatory treatment of Treasuries as only the fifth most important factor informing their decision to hold their liquidity in Treasuries.

- By contrast, foreign banks’ US operations view US Treasuries’ regulatory treatment as the single most important factor in constructing their US liquidity buffers.

New Federal Reserve Supervision Vice Chair Bowman’s June speech suggests the potential for significant reductions to large US bank capital requirements. In her speech, she stated that fixes to the e-SLR for the US G-SIBs are necessary, but may not be sufficient. Vice Chair Bowman’s speech also noted an upcoming July 2025 conference to “broaden our perspectives on bank capital requirements.” Bank investors understandably may be concerned if the Fed reduces US bank capital requirements at this point in the cycle. Is the policy intent to eliminate post GFC gold-plating of US bank capital standards? Maybe.

The main options to reduce bank capital likely to be considered are:

- remove Treasuries (and maybe reserves at the Fed) from the e-SLR, SLR and Tier 1 leverage ratio, thereby reducing capital requirements at all US banks. Removing Treasuries from just leverage standards for large banks would create an unlevel playing field for small banks and could have unintended consequences for deposit competition; or

- replace the 2% eSLR buffer with 50% of the G-SIB surcharge.

The second option likely is most interesting for the U.S. G-SIBs. It would allow them to push on the opening from Fed Vice Chair Bowman to lobby for a change in the G-SIB surcharge calculation which could afford the opportunity to reduce both G-SIB risk-based capital and leverage ratio requirements even as regulatory capital standards for other US banks don’t change. However, lowering only US G-SIB capital requirements could have both financial stability implications and negative competitive effects for smaller banks.

A bit of background on the US G-SIB surcharge calculation may be helpful to some readers. The G-SIB surcharge is based on a systemic risk score. In the US, this score is derived from two methods—Method 1, which follows the Basel Committee’s methodology, and Method 2, applicable only in the U.S. Systemic importance indicators include size, interconnectedness, cross-jurisdictional activity, complexity, substitutability (Method 1), and reliance on short-term funding (Method 2). Method 2 always results in a surcharge greater than or equal to Method 1, so the applicable surcharges for U.S. G-SIBs are determined using Method 2. The table below summarizes the current US G-SIB surcharges under both Methods.

| Current Capital Impact of Eliminating Method 2 is Large | |||

| G-SIB | Method 1 | Method 2 | Difference |

| BAC | 1.5% | 3.0% | -150 bps |

| BNYM | 1.0% | 1.5% | -50 bps |

| Citi | 2.0% | 3.5% | -150 bps |

| GS | 1.5% | 3.0% | -150 bps |

| JPM | 2.5% | 4.5% | -200 bps |

| MS | 1.0% | 3.0% | -200 bps |

| STT | 1.0% | 1.0% | No impact |

| WFC | 1.0% | 1.5% | -50 bps |

Source: OFR Bank Systemic Risk Monitor, 2024 data

Additionally, Method 1 of the surcharge calculation uses aggregate global indicator amounts denominated in euros and converted to U.S. dollars using current exchange rates. Method 2, by contrast, employs fixed coefficients for the systemic indicators. Thus, a switch to Method 1 could further reduce US G-SIB capital surcharges over time beyond what I show in the table above if market expectations for further US dollar depreciation are realized.

Bottom line – is US bank capital and stress testing too complex? Sure. But, as global investors in banks watch significant reductions in US G-SIB capital requirements against the current macro backdrop, US banks’ preeminence among investors may wane. European bank equity is outperforming US bank equity. European bank stocks are up 39% YTD vs single digit returns for US banks. Bloomberg’s market implied measures of default risk (not pictured here) are also lower for European banks than US banks.

At the same time, there is a disconnect between the handwringing about Treasury market fragility/must reduce bank capital and ongoing Fed QT. FRBNY SOMA manager Perli had laid out the case in early March of how Treasury debt limit – and its associated reduction of Treasury’s cash balance at the Fed — could make it difficult to discern where the least comfortable level of banking system reserves at the Fed might be. Perli had thought maybe it was time to stop. I also thought this was a good idea. Yet the Federal Reserve chose only to slow QT at the March FOMC meeting, but not end it because shrinking the Fed’s own balance sheet seemed more important.

The draw down in Treasury’s cash balance (a Fed liability) has ameliorated the impact of ongoing QT portfolio runoff (a Fed asset) on US banking system reserves (also a Fed liability). US banking system reserves remain ~$300 billion above the ~$3 trillion level where SVB failed in March 2023. It will be important to track what happens to bank reserves when Treasury rebuilds its cash balance at the Fed after debt limit. However, this month there also is a new incremental pressure on US banking system funding and liquidity stemming from the removal Wells Fargo’s asset cap. Small banks may choose to hold a bit more liquidity as they see how Wells’ ability to grow impacts deposits and funding markets.

- What about risks and fragilities in money markets and banks if the Fed drains too much?

- If the Treasury market is so fragile that we need to reduce bank capital, why is the Fed still letting $5 billion in Treasuries and up to $35 billion in agency MBS roll off its balance sheet every month?

In general equilibrium, the ongoing rolloff of agency MBS from the Fed’s balance sheet must be refinanced with other investors and may cheapen agency MBS in a way that reduces the attractiveness of Treasuries.

Indeed, Barth, Kohn, Monin and Sokolinskiy show that when other fixed income securities (agency MBS, CLOs) become more attractive relative to Treasuries, asset managers sell Treasuries and buy the more attractive US fixed income assets which introduces tracking error — a widening gap between portfolio duration and the portfolio’s benchmark duration. Asset managers establish long positions in Treasury futures (as opposed to holding Treasuries directly) to reduce this duration gap which, in turn, gives rise to the basis trade involving both asset managers and hedge funds. This analysis raises the possibility that ongoing Fed rolloff of agency MBS through QT may cheapen agency MBS, draw asset managers away from Treasuries and thus could contribute to Treasury market fragility.[4]

Big picture the US Treasury operating at a lower cash balance due to Treasury debt limit has had a QE-like liquidity effect in US money markets. Passage of the final US tax legislation in July is expected to include a debt limit increase. The end of debt limit could alter relatively benign money market conditions as Treasury financing needs rise and Treasury rebuilds its cash position. Bank treasurers would be wise to evaluate their term funding and liquidity as financial conditions may tighten after Treasury debt limit ends.

I wish all Treasury Talk readers a happy start to summer and hold on to your bank’s capital!

[1] The 2018 Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (EGRRCPA) permanently removed reserves at the Fed from the supplementary leverage ratios (SLRs) of the three large US custody banks – Bank of NY Mellon, Northern Trust and State Street.

[2] Banks in this category include Truist, PNC, Northern Trust, US Bancorp, Schwab, Capital One and foreign banking organizations.

[3] The last two US Financial Sector Assessment Programs from the IMF have flagged that US banks are not subject to meaningful quantitative regulation of interest rate risk in the banking book.

[4] Perhaps it was awkward for the FOMC to contemplate ending QT given that at the current level of the Fed funds rate ongoing SOMA losses make a stable Fed balance sheet possible only if the Fed maintains a small amount of Treasury runoff. Fed losses are financed with money creation and if QT were completely ended the Fed’s balance sheet would begin to grow in line with ongoing losses. The Fed’s “deferred asset” related to 2023 and 2024 operating losses now totals over $215 billion.