July 2025 –Yes, it is hard to not watch the Apprentice summer episode involving the Fed Chair. But tighter liquidity, stagflation and impacts of fiscal dominance on long-dated yields are the three key forces banks need to monitor.

I hope Bank Treasury Talk readers are having a good summer. At the start of July I had a terrific student from the spring semester email me to ask “we seem to be in a weird place …things seem steady despite tariffs… I’m curious on your thoughts.” On reading the student email, a scene from Star Wars came to mind.

A shift in macrofinancial and banking conditions is underway. What are these three key macrofinancial forces?

#1 Tighter Liquidity

First, Fed QT– getting ready for a shift from being “like watching paint dry” to tighter liquidity conditions this fall and associated risks. Tighter liquidity conditions are coming both to financial markets and banks. Since February the US Treasury drawing down its cash balance at the Fed due to debt limit has added $500 billion of liquidity to the financial system. Congress’ early July passage of the OBBB act also included an increase in the debt limit – how could it not? So, Treasury will begin to increase its T-bill issuance and build up its cash balance again to its typical 5-day operating target, draining liquidity that was helpfully offsetting ongoing Federal Reserve quantitative tightening (QT).

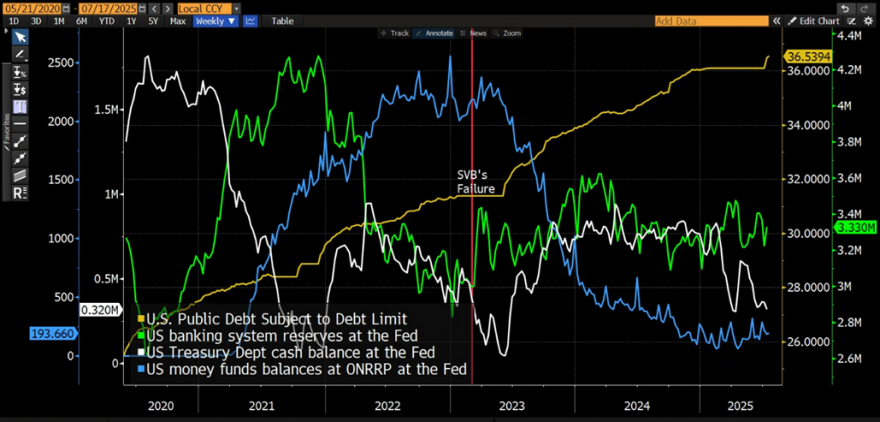

There are three main types of liabilities on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet –

1) reserves in the banking system (green line),

2) Treasury’s cash balance (white line) and

3) money fund balances the Fed’s ON-RRP facility (blue line).

ON RRP has acted as a notable offset to QT since SVB’s failure. However, now there is only about $200 billion in ON RRP balances from money funds at the Fed. Therefore, Treasury increasing its share of Fed liabilities through debt issuance to rebuild its cash position will necessarily pressure bank reserve balances at the Fed and liquidity. US banking system reserves are currently at $3.3 trillion, or about $300 billion above where SVB failed.

Foreign banks hold an outsized $500 billion of the $3.3 trillion in reserve balances at the Fed, reflecting both the US dollar’s higher yield and perhaps also worries about the future availability of US dollar swaps lines to foreign central banks in their home countries in a changing world order. The distribution of reserves is relevant if foreign banks’ US operations are less inclined to redistribute liquidity to domestically chartered US banks.

Treasury has signaled that it will proceed cautiously on increasing the cash held at the Treasury General Account. After the debt limit increase in early July, Treasury announced it would aim to raise its cash balance to around $500 billion by the July 30 Quarterly Refunding Announcement (QRA). A typical Treasury cash balance at the Fed would be about $800 billion. As of writing, the TGA balance still sits at ~ $325 billion, indicating that Treasury is moving carefully.

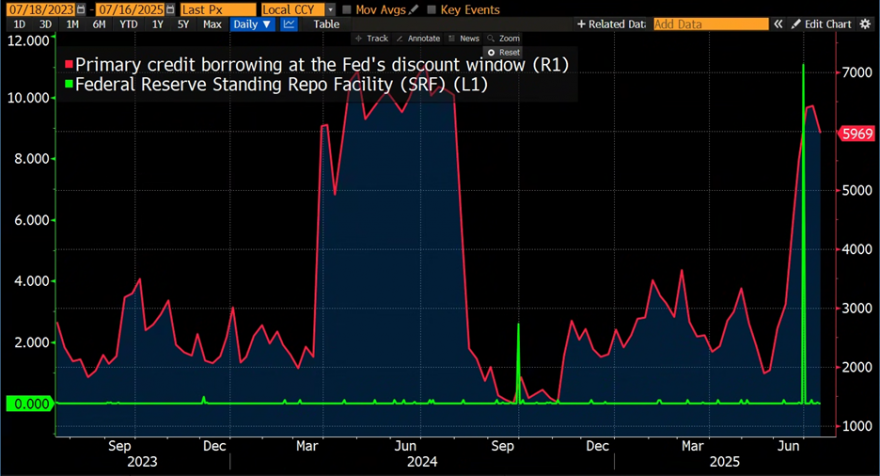

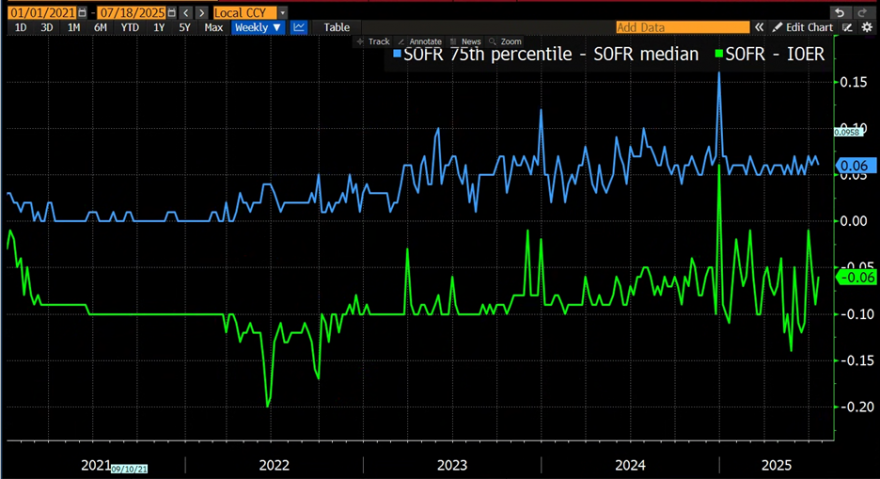

Such caution is warranted. There is some evidence of banking sector liquidity tightening already. A rise in discount window lending (red) and increased use of the Fed’s standing repo facility (green) at Q2 quarter end are notable.

The spread between SOFR’s 75th percentile and median trades and the spread between SOFR and IOER are widening, indicative of some rising pressure in US money markets even with no normalization of Treasury balances at the Fed having happened yet.

From here – if Treasury does normalize the cash balance — liquidity conditions will start to become notably tighter in banks and financial markets into late summer and fall. The unfolding situation shares some unfortunate parallels with the run up to the 2019 repocylapse and even SVB’s failure. Unconventional monetary policy is easy on the way into banks and financial markets, but very difficult to unwind smoothly. This is particularly true in the US because fiscal deficits continue to expand the size of the Treasury market and quantitative guardrails guiding the supervision of interest rate risk at US banks are non existent.

Do I sound negative about risks of unconventional policy tightening? To quote the IMF’s Oct 2024 Global Financial Stability Report,

the key risk is that quantitative tightening may drain bank reserves too much, causing the type of squeeze in funding markets exemplified by the US repo market turmoil in September 2019. Currently, many central banks are engaging in QT simultaneously, raising the odds that this type of risk can spill over more widely – for example, inadequate banking reserves in one jurisdiction may end up impacting conditions in another.

Proposals earlier this year that floated from the SOMA team at FRBNY to end the Fed’s QT2 were on target. But, the FOMC instead elected to taper QT, not to end QT. Thus, the consequences of most of the FOMCs’ poor grasp of the Fed’s balance sheet and its interaction with the financial sector may become evident again soon.

It is noteworthy that this week FRBNY published two blogs recapping the history of Fed repo operations. My inference is that at least some parts of the Fed are seeking to prepare public opinion/media for when it becomes necessary to spray some standing repo facility (SRF) foam down on the proverbial runway because bank reserves are no longer abundant.

#2 – Stagflation risks to banks

So who cares whether the Fed provides liquidity to banks through reserves balances or the SRF? This question brings me to a second key force — official sector actions that unfortunately weaken US bank loss resilience even as the challenge of stagflation comes into view.

Banks’ reserve balances at the Fed are a bank asset/Fed liability. Reserve balances result in banks earning interest income from the Fed. By contrast, SRF is a bank liability/Fed asset. SRF usage results in the banks paying interest to the Fed. Therefore, a drawdown in banking sector reserves at the Fed that hypothetically could be replaced with semi-sustained bank SRF usage reduces US bank profitability. Clearly such a move would not be as bad as eliminating all of IOER which some members of Congress have floated, but operating in a regime where reserves are no longer abundant is still an official sector move that reduces bank profitability.

Recall also that banks must sign up for the SRF (current list of SRF eligible banks available here) and that the SRF also is only available to banks with assets > $10 billion. Seemingly, a world of less than ample reserves leaves community banks reliant on the Fed’s discount window. Hopefully, the discount window will be more ready than it was in 2023. But SRF or discount window borrowing from the Fed still is a cost to US banks as opposed to an earning asset like reserves. Profitability is banks’ first buffer against loss.

Interestingly, a weakening of core US bank profitability is a theme from Q2 US bank earnings season. A number of US banks (BAC, JPM, WFC, USB, M&T) reported a deterioration in Q2 net interest income (NII) or revised down forward looking NII guidance. For some banks, the NII deterioration relates to deposit pricing pressures; for other banks weaker NII stems from lower yields/less pricing power on new loans.

So, greater bank borrowing from the Fed may be coming into view and core US bank profitability is weakening. At the same time, US G-SIB capital deregulation is gathering steam. Next week, the Federal Reserve Board will host an invitation-only conference to discuss its planned reductions in US G-SIB capital (so, no audience questions unless you got a golden ticket from Willy Wonka!).

My June column expressed concerns about the risks associated with a significant reduction in US G-SIB bank capital with stagflation risks coming into view. Some in Washington DC maybe looking ahead to fiscal stimulus to strengthen the US economy in 2026 and believe the risks to US banks associated with lowering capital requirements, therefore, will be limited.

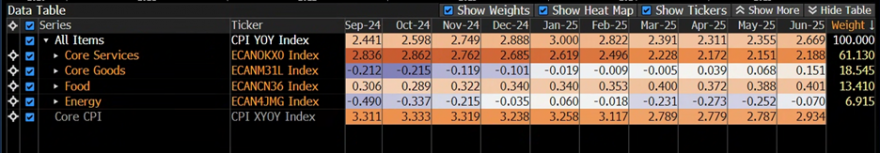

But before the US economy gets a OBBB act fiscal impulse in 2026, US banks will face a stagflationary environment. Stagflation risks now are starting to come more clearly into view. June CPI rose 2.7% y/y from 2.4% y/y in May and showed an acceleration across all categories, including core goods related to tariffs.

Reduced immigration and ongoing shrinkage in the labor force due to aging demographics may also be expected to impact service inflation more in coming inflation releases. Core PCE remains above the Fed’s target and the median survey estimate for June core PCE due out on the eve of the July FOMC meeting is 2.7% y/y. As measured by core PCE, inflation has been above the Fed’s 2% target for more than four years.

Stagflation is the toughest macroeconomic environment any banking system can face. In a stagflationary environment, credit, liquidity, and interest rate risk can all manifest simultaneously and pose stress. This is why official sector actions to reduce US G-SIB capital could look very ill-advised/foolish if the sector is stressed from stagflation showing up on the scene in H2 2025.

#3 Fiscal dominance

The final and most important force is ongoing fiscal excess which, ironically, the Fed helped enable. Sadly, fiscal dominance now contributes to undermining Fed independence. The headlines around the President Trump firing Chair Powell are constant – and yet, if it happens, one should still expect negative market response.

Various candidates to replace Chair Powell regularly make statements to advance their candidacy for Fed Chair so that it does seem like we all are watching an extended summer episode of The Apprentice. These statements, including about cutting rates at the July FOMC meeting, don’t need repeating. It should be obvious that the Fed should not cut interest rates with inflation still above target and accelerating.

Yes, tariffs are a one-time shock, but labor supply is shrinking even as Social Security benefits increase the likelihood of a subsequent CPI indexation induced “echo” of tariff inflation in subsequent quarters as happened after Covid. Personally, CPI in the high 3s or low 4s in the coming months would not surprise me (note that I am long TIPS).

The current environment risks being akin to Covid, i.e., (tariff induced) supply shocks coupled with coming fiscal stimulus risks that above target inflation just keeps going. Rather than pressure the Fed, Congress should work on comprehensive fiscal deficit reduction, including and especially Social Security and Medicare reform.

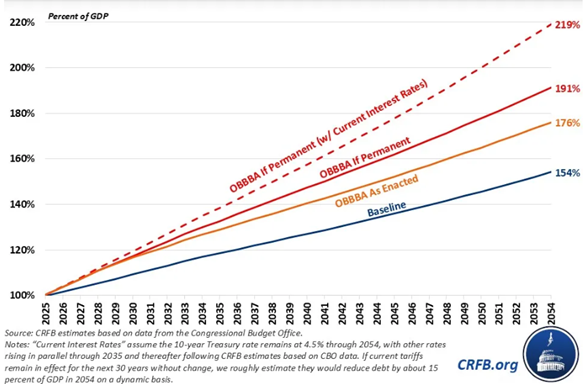

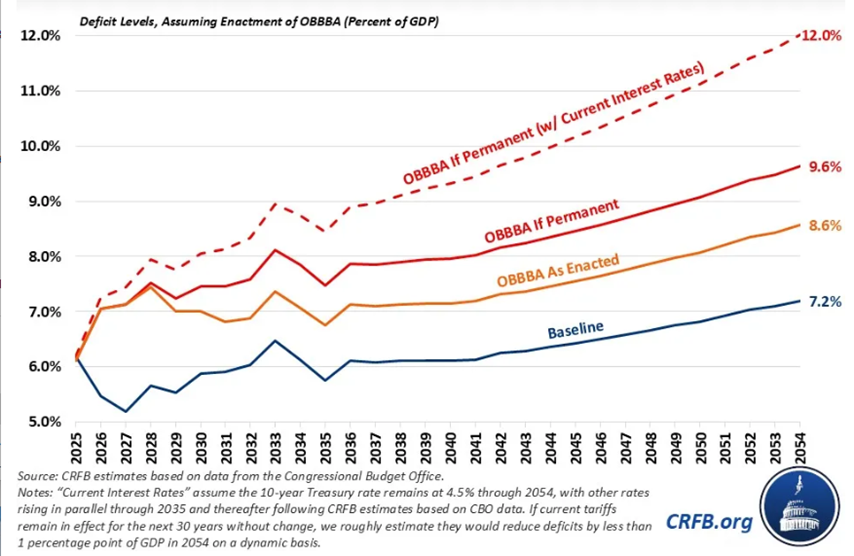

At bottom, the Administration wants the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates given the fiscal pressure the current level of interest rates place on US government finances. My thanks to the Committee for a Responsible Budget for sharing their concerning projections for US government debt/GDP and the deficit to GDP post the OBBB Act based on CBO’s scoring (which notably assumes a 3.6% 10-year Treasury yield over most of the projection period).

But if the Fed cuts interest rates, a risk is that Congress may use this newfound “fiscal space” to 1) make OBBA permanent, 2) fund still more tax cuts that favor wealthy older Americans, or 3) further delay needed changes to so-called entitlement programs which soon will be insolvent. While they approach their budget deficit expansions differently, US politicians of both parties seem unwilling to undertake the hard work of deficit reduction. QE made budget deficits seem costless and resulted in Chair Bernanke winning a Nobel prize. It all looks a bit less brilliant now with Chair Powell’s job on the line, US budget deficits widening ever more, and stablecoin and crypto legislation sailing through Congress fed by concerns about dollar depreciation.

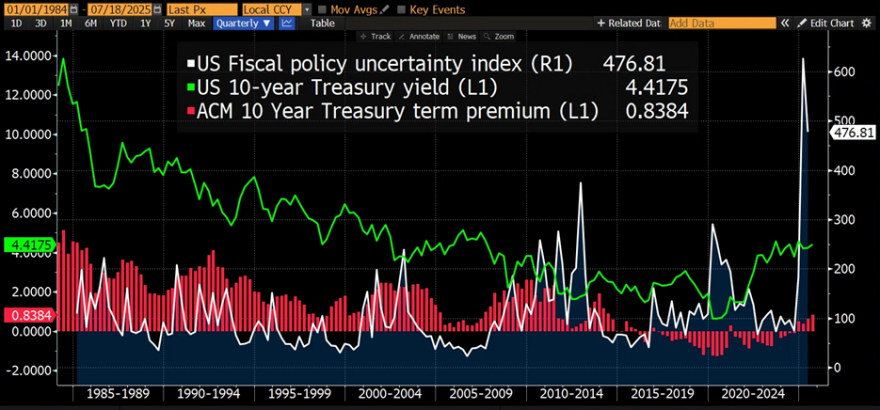

Fiscal space possible Fed rate cuts also assumes, of course, that the 10-year Treasury term premia doesn’t continue to rise and offset reductions in the Fed funds rate. Significant Fed rate cuts would typically point towards a lower 10-year Treasury yield (given forward rates), but it is plausible that could be offset by a rise in the 10-year Treasury term premia (red).

Under new leadership, the Fed could, of course, resume QE to bring long-term yields down. But, Fed QE would devalue the dollar, embed a risk premia in US assets and support further gains in cryptocurrencies and precious metals. Banks should brush up on the destabilizing impact of QE on their balance sheets – a topic I teach about in BTRM. FRBNY published a blog this month on the topic of QE’s destabilizing impact on banking sector deposits.

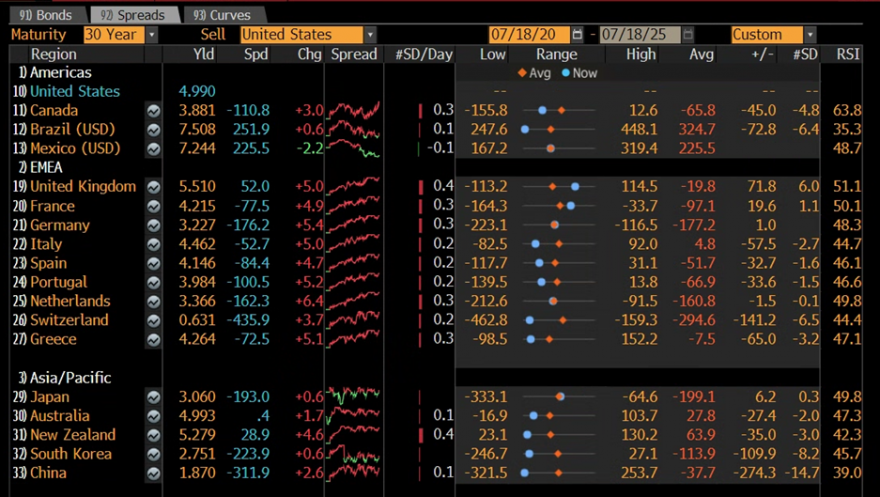

Fiscal dominance clearly is a problem in the US, but it also is in some other advanced economies. As can be seen below, 30-year government bond yields sit at or near highs for many – but not all — advanced economies. Unfortunately, it does feel like a bit of a race between the US, UK, Japan and France to see whose bond market will come unglued and spillover on to others’ markets first. That said, I appreciate French Prime Minister Bayrou for having the courage to propose measures to begin to whittle France’s budget deficit down.

It is also notable that countries that have undertaken fiscal adjustment (like Portugal, Greece and Spain) have improved their 30-year government bond spreads to Treasuries or countries with low government debt to GDP (Switzerland, Canada, Germany) also have relatively favorable spreads to the 30-year US Treasury.

Ok, concerning- but do banks really need care if fiscal policy runs amok? Yep, history suggests inflation, interest rate caps, capital controls and other measures of financial repression affecting financial institutions are common when government debt to GDP becomes elevated. In the current context, we know that policymakers want both banks and stablecoins to help fund the rapidly growing Treasury market…sometimes history rhymes.

I wish all Treasury Talk readers an enjoyable summer and keep eyes on your bank’s liquidity, earnings and capital!