November 2025 – Failing unconventionally: Both the US Treasury (government shutdown & greater reliance on T-bills) and Fed (QT “forward guidance”) are tightening USD financial conditions, affecting banks and the economy

I hope Treasury Talk readers had a fun and safe Halloween holiday.

However, if you were working in bank treasury it is possible that Halloween was a bit of a low-grade nightmare on ALM street. Risks from policy errors are rising and so are front-end USD rates despite ongoing Fed cuts.

What do you do when one of your macrofinance students from the spring writes:

“Hi, Professor Cetina, I was reading and I am curious about your thoughts on Fed balance sheet right now…”

Well, particularly given developments, you sit down and write back. Here goes:

Headed into October FOMC, I had recommended the Fed do two things with regards to QT.

- First, I suggested that the Fed immediately end QT in October. Reserve balances at the Fed were ~ $3 trillion when SVB failed and that is basically where reserve balances at banks had fallen to in early October.

- Second, I also had suggested that the Committee close the ON RRP facility to guard against the risks to bank liquidity associated with a hawkish repricing of US rate expectations. A repricing of US rate expectations could cause money funds to move cash into the Fed’s ON RRP facility and further drain banking system reserves. This dynamic of bank reserves no longer being abundant and quickly becoming scarce due to sharp growth in money funds ON RRP balances because of a hawkish repricing of market expectations was operative when SVB failed in the spring of 2023.

The FOMC did announce an end to QT at its October meeting which was a lot quicker than Chair Powell suggested in his October NABE speech. However, the FOMC decided that Fed balance sheet runoff will not end until December 1.

The FOMC also announced reinvestment of agency MBS and agency CMBS principal maturing into T-bills. These operations will not begin until December 11th. There are more details about these operations (whether it is forecast vs actual principal repayment, maturity distribution, etc) available on FRBNY’s website here. But big picture, at the October meeting the FOMC announced that QT does not fully end until December 11th, i.e., right before year-end.

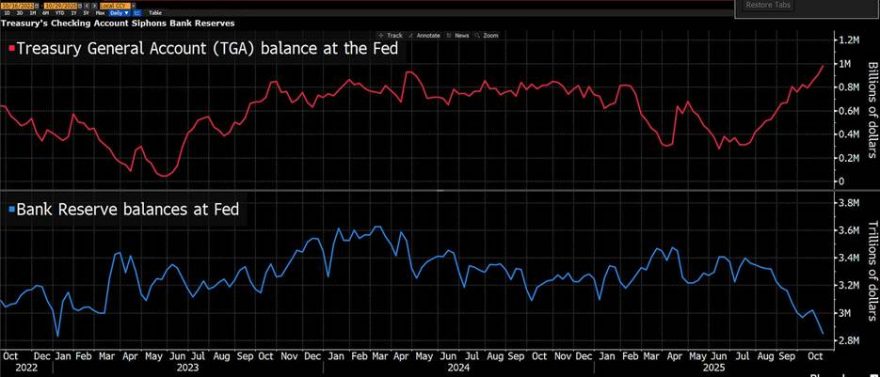

We ended this week with US banking system reserves (Chart 1, blue) down sharply to $2.83 trillion.

This piece will discuss how now BOTH Federal Reserve and Treasury Department errors are combining to increase macrofinancial risks for USD money markets, fixed income and the banking sector. Big picture — tighter banking sector liquidity increases both short-term interest rates and reduces loan growth which seems in conflict with both the FOMC and Administration’s stated policy objectives. Sadly, this state of affairs fits with the theme that the consolidated public sector’s footprint has become too large and complex as a result of fiscal dominance, missteps can be quite costly and a significant source of macrofinancial risk.

Turning first to the Federal Reserve,

Most central bankers appear to believe that QE and QT are policies that operate in a symmetric manner. But QE and QT are not symmetric. October’s FOMC illustrated one example of their policy asymmetry. Unlike QE, forward guidance does not work with QT. Why? Announcing that in the future banking sector liquidity will no longer continue to tighten does not alleviate today’s real-world system wide balance sheet constraints affecting banks, repo and US fixed income markets.

Why can’t banks just hang on and adjust to a lower level of central bank liquidity until December?

- #1 Bank business models have adapted to higher levels of liquidity that an expanded Fed balance sheet provided. Some banks may not have recognized how QE liquidity could become ephemeral. Thus, shrinking bank liquidity at the Fed can disrupt some banks’ business models. For example, think about the $1 trillion in undrawn liquidity commitments from US banks to NBFIs.

- #2 US banks still have ~$400 billion in unrealized securities losses which imply that balances at the Fed are important liquidity that some banks understandably desire to hold on to. It seems that weak oversight of interest rate and liquidity risk at banks and forbearance around these topics since 2023 actually has a cost beyond bank failures. The costs include a structurally higher central bank balance sheet and the associated Fed interest cost on those interest-bearing liabilities. The Fed significantly underpricing the BTFP probably did not help incent some banks to take these risks seriously either.

- #3 US Treasuries outstanding also are growing too rapidly relative to the base level of liquidity in the banking sector to fund it (more on this point later).

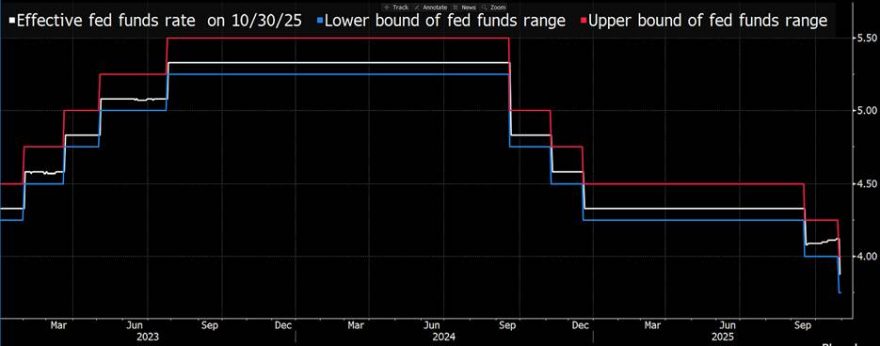

Another painful misstep was that while the Fed cut rates by 25 bps at the October meeting, Chair Powell’s comment about the future rate outlook was hawkish. To be clear, I agree that the Fed should not cut rates in December. However, as I have written previously, the Fed currently controls only the size of its balance sheet, not the composition of its liabilities. Even as Fed fund futures have repriced to lower the probability of future rate cuts, balances in ON RRP have ticked up from $2 billion last Friday to $52 billion this Friday, accelerating the ongoing drain of US banking system liquidity. It was appropriate to be more hawkish about a December rate cut, but the FOMC then needed to close the ON RRP too.

Halloween was both month-end for all banks and year-end for Canadian banks. The sharp reduction in banks’ reserve balances has increased bank borrowing from the Fed. US banks’ discount window borrowings through Oct 29th totaled about $7 billion (Chart 2, red line), near year-to-date highs. We do not yet know the magnitude of Halloween discount window borrowings (data out next Friday).

We do already know that the 40 large banks’ use of the Fed’s standing repo facility (SRF) rose sharply on Halloween. One notable feature of the Halloween SRF uptick to $50 billion (Chart 2, green line) was that the increase in banks’ SRF utilization came late in the day. I was attending a conference in Canada over Halloween. On Halloween morning I checked in and noted $20 billion in SRF borrowing, but by trick-or-treat time at the end of the day the volume of SRF outstanding had increased markedly to $50 billion. It seems like there were one or more banks with a decent size late in the day borrowing need, so I am curious to see the SOFR and effective Fed funds rate prints from Halloween on Monday morning…

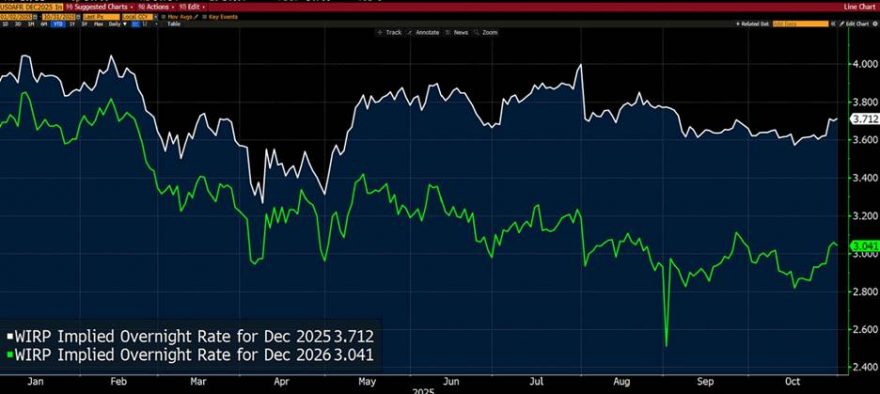

As already noted, money fund balances at the Fed’s ON RRP facility ticked up this week from almost zero to $52 billion (Chart 3, purple line) due to a hawkish repricing of rate expectations (Chart 4, green line Dec 2026 and white line Dec 2025 implied overnight USD rate expectations). The ON RRP really should have been closed.

Finally, the FOMC also effectively announced that it would cheapen agency MBS securities through allowing its $2 trillion in agency MBS holdings to runoff over time and be reinvested in T-bills. Ironically, Fed cheapening of agency MBS may prove to be a factor contributing to Treasury market fragility. Recall that the basis trade in Treasuries begins because bond fund managers buy other fixed income assets like agency MBS and use Treasury futures to keep their duration close to their benchmark’s duration. Yes, hedge funds use repo funding from banks to buy Treasuries and lever up a convergence trade of the cash-future basis. However, the initial private sector decision that gives rise to the basis trade is the decision on the part of bond fund managers that they prefer to take risk/generate return via being long agency MBS as opposed to being long Treasuries. The impact of the compositional shifts in the Fed’s balance sheet on relative prices across USD fixed income and private investors’ portfolio allocations merits study. But overdoing it with QE reduces the attractiveness of duration/positive convexity as a source of fixed income investor return. In this way, QE may have actually perpetuated the very Treasury market weakness it has purported to alleviate.

As I noted in June, Barth, Kohn, Monin and Sokolinskiy show that when other fixed income securities (agency MBS, CLOs) become more attractive relative to Treasuries, asset managers sell Treasuries and buy the more attractive US fixed income assets which introduces tracking error — a widening gap between portfolio duration and the portfolio’s benchmark duration. Asset managers establish long positions in Treasury futures (as opposed to holding Treasuries directly) to reduce this duration gap which, in turn, gives rise to the basis trade involving both asset managers and hedge funds. This analysis raises the possibility that Fed disinvestment from agency MBS may cheapen agency MBS, draw asset managers away from Treasuries and thus could contribute to Treasury market fragility.

The Treasury Department also co-owns overtightening bank liquidity and tightening USD financial conditions.

First, it now seems that the government shutdown and associated lack of Treasury/government spending are a new factor that has accelerated the drawdown in banking system reserves at the Fed. Since I published my American Banker op-ed on this issue, Treasury’s cash balance at the Fed, or TGA, has risen to almost $1 trillion, well in excess of Treasury’s current operating TGA target of $850 billion.

The longer the US government shutdown continues the more pressure on banks, money markets and fixed income markets through this channel of Treasury draining cash from the economy via not making planned expenditures and de-facto locking cash up at the Fed.

There is a straight-forward fix to Treasury holding almost $150 billion at the Fed above its TGA target and draining bank reserves. That fix is to restart the former Treasury Tax & Loan (TT&L) program which is when Treasury lends out “excess” balances to the US banking sector. Reactivation of TT&L is especially crucial if the government shutdown extends much further though the Treasury and Fed have let the program gather a lot of mothballs. Banks even could begin to ask Treasury and FRBNY about it!

Based on the above, one might conclude that TGA-related pressure on bank liquidity and, relatedly, repo markets will abate when the government shutdown one day ends. However, the Treasury Department also is creating structural pressures that will keep TGA balances elevated relative to its current TGA target of $850 billion.

This brings me to a second Treasury Department policy mistake. Specifically, the Treasury Department will conduct its Quarterly Refunding Announcement (QRA) next week. It is expected that the Treasury will announce plans to up its T-bill issuance. Next week’s Treasury QRA could see Treasury guide the bond market towards that it will increase T-bills from 20% of debt outstanding to 25%. In essence, the Administration seems ready to fund a structurally higher budget deficit in 2026 through T-bill issuance as opposed to across the Treasury curve. Recall that Treasury Secretary Yellen was criticized by now Fed Governor Miran for this in 2024, but the policy of a shorter weighted-average-maturity (WAM) of the Treasury market continues! There are real risks to Treasury doubling down on this strategy, including inflation rising further in H1 2026.

But a greater T-bill issuance implies a higher Treasury cash balance target as Treasury needs more cash in the TGA given greater rollover risk. Such T-bill issuance and associated higher TGA is a greater liquidity drain from banks. This recent Treasury policy speech would seem to dispel any questions that Treasury would change its cash balance policy at the QRA next week. So, a permanent increase in Treasury’s cash balance at the Fed is coming given the expected higher T-bill share and greater rollover risk of T-bill funding and, in turn, a permanent drain of US bank liquidity at the Fed. Maybe the $1 trillion TGA balance stays where it is even after the government shutdown ends? So, in this fashion, the Treasury is also contributing to the over-tightening of bank reserves through its own drain via the TGA. How good is the Treasury at assessing banking sector liquidity? My guess is less well-equipped than the Fed.

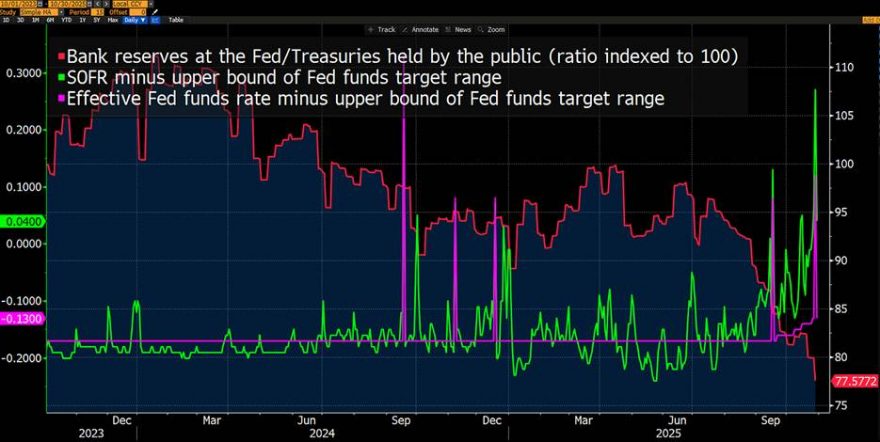

All of this implies that the risks are high of even more liquidity strains coming into view for banks and money market into mid-December. Large banks are very important sources of liquidity to Treasury market trading. We know that large US banks help fund the basis trade by providing hedge funds with repo funding. It does appear that the base level of liquidity in the banking sector has shrunk very rapidly and is now too low given the recent and prospective growth in outstanding Treasury securities. The contraction in bank liquidity relative to outstanding Treasuries (red line, indexed to 100 at series start) is associated with upward pressure on SOFR (green line) and even the effective Fed funds rate (magenta line) relative to the upper bound of the Fed funds target range.

How did the FOMC and Treasury both get this situation so wrong?

- Current and former FOMC members often talk about bank reserves relative to GDP. I am skeptical that this is a useful way to think about the problem. What seems more relevant is bank reserves at the Fed relative to Treasuries (red line). Effectively, the Fed’s balance sheet through providing liquidity to the banking sector is what keeps the basis trade going and permits smooth growth in the Treasury market. In a very real sense, the Fed continues to aid a fiscal authority that does not want to narrow the primary budget deficit (expenditures ex-interest payments minus government receipts/taxes). Chair Powell noted that the Fed’s balance sheet and, by extension, bank reserves would begin to grow again in December. In so doing, the Fed sows the seeds of the end of its independence. It is reasonable to expect that the Trump Administration will aim to realign Fed leadership to lower interest rates to narrow the budget deficit. Like other administrations, the Trump Administration finds it politically easier to not meaningfully address the primary budget deficit. Getting the Fed to lower interest rates is a preferred approach to reigning in the budget deficit.

- Treasury has this wrong because it believes that stablecoins will create significant new demand for T-bills and understandably dislikes a bloated Fed balance sheet. Per Defi Llama, there is only about $100 billion in USD stablecoin growth YTD to a total USD stablecoin market cap of ~$307 billion, not all of which is invested in T-bills. Stablecoins will create some modest new demand for Treasuries, but most of the incremental T-bill demand will come from the Fed. Again, to the extent that Fed agency MBS runoff into T-bills skews MBS returns higher and renewed Fed balance sheet expansion reduces Treasury returns — the cycle of investors going into other fixed income assets and out of Treasuries continues. Upward pressures in front end rates due to insufficient bank reserves also can disincentivize money funds from investing their cash in T-bills and skew them more towards to investing their funds in ON RRP until the dust settles — pulling cash out of the financial system.

Appendix: money market charts

SOFR vs IOER rising; SOFR outside of upper bound of Fed funds target

Spread of SOFR vs effective Fed funds rate — 17 bps

Effective Fed funds rising within the Fed funds target range

What does this mean?

Big picture — look for liquidity pressures at banks, money market volatility and front-end rates to remain elevated into year-end despite the Fed’s October rate cut and an “end to QT.” Treasury TT&L could also help near-term. Banks asking the Treasury Department and Fed about TT&L could help move a discussion of this short-term fix along.

The Fed will restart QE soon. The Fed believes the growth in its balance sheet will be modest/incremental. I am skeptical. I suspect Fed balance sheet growth will need to be large because bank liquidity was excessively tightened and to enable a larger 2026 budget deficit. Note that I am not a fan of unconventional monetary policy. I view unconventional monetary as an enabler of poor fiscal policy and a key factor helping to undermine central bank independence globally.

Wishing Treasury Talk readers a good transition into Q4 and the holiday season!