October 2025 – A Nightmare on ALM Street or a Happy Halloween this October?

Halloween is just around the corner. But will it be like a scary horror movie or a more fun-filled holiday seems a pertinent question with evidence of both rising liquidity and credit risk in the banking sector.

Halloween is just around the corner. But will it be like a scary horror movie or a more fun-filled holiday seems a pertinent question with evidence of both rising liquidity and credit risk in the banking sector.

This month’s Treasury Talk column will discuss three Halloween jump scares in the US financial sector:

1) over-tightening of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet;

2) concerns non-depository financial institution (NDFI) ALM challenges with a focus on NDFI’s intersection with corporate credit in particular given recent Tricolor and First Brands credit events; and

3) what both factors mean for banks.

I am not a fan of horror films. So this month’s column concludes with some recommendations of actions that both US policymakers and banks could take to have a happy Halloween.

Turning first to the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, one of the lectures I give in BTRM is about the connections between unconventional monetary policy and bank assets, liabilities and regulatory metrics. BTRM’s founder, Moorad, has jokingly referred to this as a lecture on the “dark arts” of central banking and why it matters to banks – a seasonally appropriate comment!

Jump scare #1 – The Fed’s balance sheet has been left too long on auto pilot again with the need for an abrupt adjustment now coming into view.

Even as the FOMC cut interest rates in September, presumably to loosen US financial conditions and provide accommodation, the Fed was draining too much banking sector liquidity through QT and starting to tighten US financial conditions.

I have written previously in my Treasury Talk column this year about the risks ongoing QT would pose to bank liquidity and funding in Q4. I also noted in a July interview in Moorad’s ‘Straight Talk’ column that “ongoing Federal Reserve balance sheet runoff, so-called quantitative tightening (QT), will become more noticeable in its impact on the financial sector later this year” and recommended banks evaluate building term funding and liquidity over the summer.

The September FOMC minutes released just a few weeks ago contained no meaningful discussion of QT and suggested no Fed urgency to end it. Last week I wrote an op-ed in American Banker arguing that Powell may actually be ‘too late’ when it comes to ending QT. In the op-ed I noted that it is true that unconventional monetary policy has continued for too long and contributes to income inequality, permits fiscal largesse, and raises dollar debasement concerns. However, excess FOMC sensitivity to criticism and the desire to placate the Administration in a heated race for Fed Chair may have contributed to the FOMC’s 2025 QT overshoot to the detriment of banks. Bluntly, the past statements of several current contenders on the FOMC to be the next Fed Chair have not demonstrated the inspired judgment on the Fed’s balance sheet that one would hope for in a new Fed Chair. I also noted in my op-ed that some banks report continued operational problems with discount window access, specifically staffing and use of automated access.

Now both money markets and other indicators suggest that Fed may have over-drained liquidity from the US banking system and, in turn, impacted banks’ liquidity provision to repo markets. Let’s take a tour via several charts.

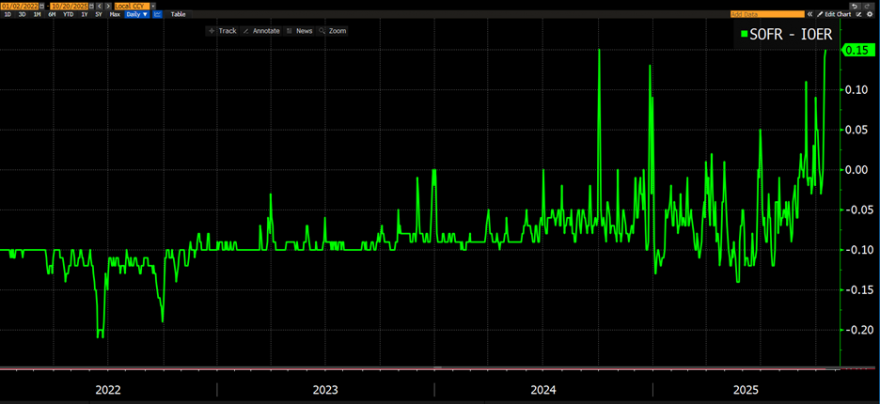

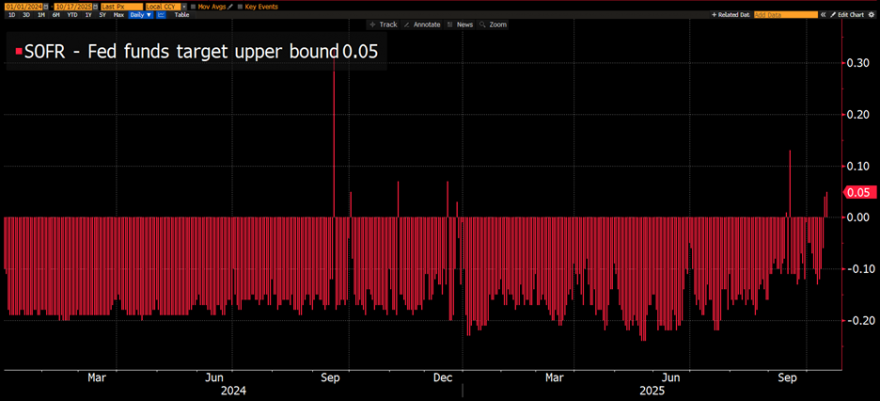

First, the spread between SOFR and interest on reserves (IOR) has widened notably.

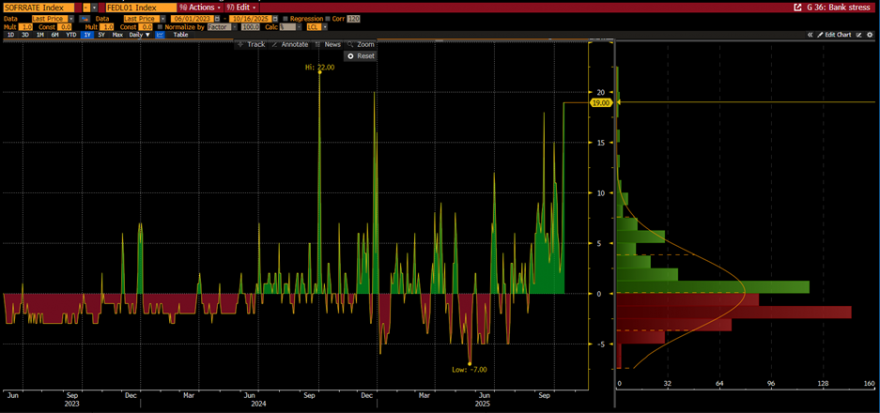

Second, the spread between SOFR and the effective Fed funds rate widened to 19 bps late last week, a significant gap.

SOFR also has begun to exceed the upper bound of the Fed funds target range.

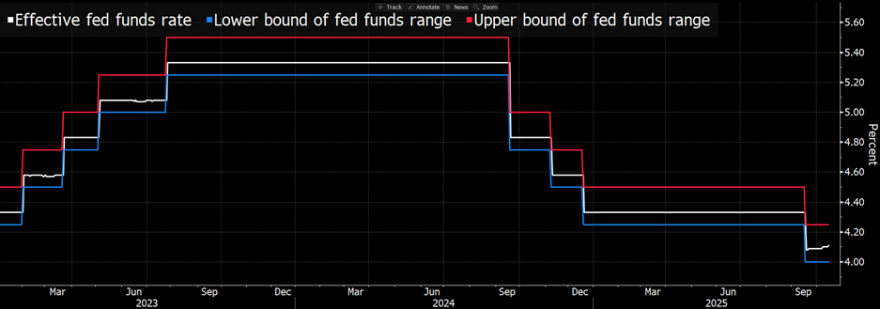

Although the effective Fed funds rate is still within the target range, pressures in SOFR stemming from ongoing QT have edged the effective Fed funds rate (white line) up three times this month, which is unusual.

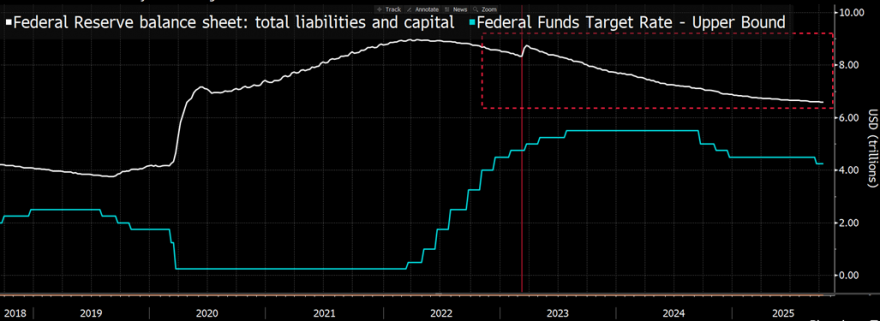

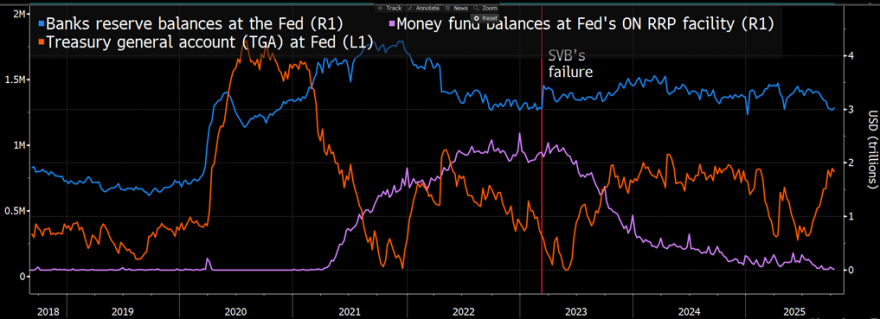

At a high level, while QT has been going on for some time, until recently much of the shrinkage in the liability side of Fed’s balance sheet (white line, Chart 1) had come through a shrinkage in the money fund balances at the Fed’s ON RRP facility (purple line, Chart 2). Banks’ reserve balances at banks are now back to $3 trillion (blue line, Chart 2) which are the levels in 2022 that US banks started to report funding strains and that preceded SVB’s failure in March 2023.

Banks’ use of both the discount window and the Fed’s standing repo facility are also rising. In sum, banking system liquidity may no longer be abundant and soon may not be ample.

Jump scare #2 – Non-depository financial institutions (NDFIs) lending to US corporates face ALM challenges.

It is well known that NDFI credit intermediation in the US has grown sharply over the last decade. My main area of focus in this column is NDFI lending to US corporates. While I recognize that there are other kinds of NDFI lending, I think this form of NDFI lending is the most important because shocks to NDFI lending to corporates could quickly spillover to banks and, in adverse scenario, the US labor market.

Two factors arguably contributed to NDFI corporate lending growth.

· First, the 2013 US bank supervisory guidance on leveraged lending was highly influential to NDFI growth in the US – not excessive bank capital regulation. Research indicates that US banks reduced their own leveraged lending, but this supervisory change did not necessarily reduce bank risk. The business of corporate leverage lending instead migrated to non-banks which, in turn, came back to banks to fund and provide contingent liquidity needed to support the NDFIs’ lending activity. Consistent with this research, one large private creditor investor described to me at a lunch in Q1 the US bank leveraged lending guidance as one of the most impactful factors in NDFIs’ success and asset growth.

· Second, the shift in the macrofinancial environment also helped consolidate leveraged lending to corporates in NDFIs. Positive US interest rates began to increase the value of mostly floating rate NDFI corporate assets. QE created a less steep yield curve which enabled NDFIs to borrow to fund themselves without paying a meaningful term premium. Successive rounds of QE also gave US banks substantial liquidity to on-lend to NDFIs while the adoption of quantitative liquidity regulation in the US, the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), remained narrowly circumscribed to only the largest US banks.

Era of NDFI growth — 2013 to 2022 – Leverage lending guidance kicks starts it. Growth also supported by QE drove down the term premia and generated ample liquidity at banks even as the policy rate moved back into positive territory in 2015 and even more positive territory after 2022 inflation shocks.

Mostly favorable NDFI ALM environment

-

The asset values of SOFR-linked loans to corporates rose.

-

Profitability and market capitalization rise.

-

NDFI credit ratings upgraded/improve.

-

Debt issued for term funding with Treasury term premia low or even inverted to short rates.

Possible era of NDFI ALM nightmare — 2026? – Losses from fraud, credit stress on corporates from tariffs and associated margin compression, rates expected to fall sharply, an anticipated steepening of the yield curve, QT becoming binding on US bank liquidity, and QE-era abundant bank liquidity fallen out of policy favor.

-

SOFR-linked asset values fall.

-

NDFI profitability and market capitalization fall.

-

Steeper Treasury curve and lower NDFI credit ratings makes debt issuance more costly.

-

Smaller NDFI borrowers experience credit issues due to margin compression from tariffs.

-

Credit problems at NDFI portfolio companies grow.

-

Credit problems are now more difficult for NDFIs to refi/extend and pretend.

-

NDFIs may have a senior position/more credit protection to same corporate obligor than some banks.

-

NDFIs may draw on bank lines.

Jump scare #3 – The combined effect on potential liquidity and solvency shocks to US banks

Recent US bank regulatory data revisions (thanks to the FDIC for its diligence!) show that US banks’ drawn exposures to NDFIs have grown quickly to $1.7 trillion (red line below). US banks’ undrawn but committed lines to NDFIs add ~$1 trillion in additional contingent NDFI exposure. US banks’ $2.7 trillion in C&I loan exposures also could be adversely impacted if NDFI leveraged corporate credit provision has weakened materially bank underwriting and/or NDFI exposures have subordinated bank claims to same corporate obligors.

In June, the Federal Reserve released the results on the 2025 CCAR stress test. Per the CCAR stress test, the 22 large banks subject to the test this year were found to have “sufficient [risk-based] capital to absorb loss.”

Additionally, box #2 of 2025 CCAR stated that “the [US] banking system is able to withstand the additional credit and liquidity stress related to NBFI sub-sectors.” To be precise, 2025 CCAR focused on whether the 22 covered US banks’ risk-based capital ratios could absorb estimated credit losses on NDFIs and potential increased capital needed to support drawdowns by NDFIs on undrawn lines and commitments.

Having previously chaired a Basel Committee research group on capital and liquidity interactions in bank stress tests, I thought CCAR’s analysis was way too narrow to pronounce all clear on risk for the US banking sector.[1]

· First, banks also are subject to leverage ratios. CCAR focuses on CET1 capital requirements. Over time the stress test essentially has morphed into an exercise to size US banks’ stress capital buffers. CCAR does not evaluate covered banks’ ability to meet their supplementary leverage ratio or Tier 1 leverage ratio requirements under stress. Leverage ratios effectively are ignored/not treated as binding regulatory constraints under CCAR even though covered banks must meet these capital standards in the real world.

· Second, there is AOCI which is not treated uniformly across US banks. Specifically, what about the intersection of potential NDFI losses and the US banking industry’s $400 billion in unrealized securities losses? Among CCAR banks there are large differences in the treatment of AOCI/unrealized AFS securities gains/loss on regulatory capital due to “tailoring.” While the nine largest US banks’ risk-based regulatory capital measures account for AOCI and unrealized AFS securities gains/losses, the regulatory capital measures of 13 other Category III and Category IV CCAR covered banks do not.

· Third, there is bank liquidity. CCAR covered banks’ on-balance sheet liquidity was not considered as part of the supervisory stress test. Specifically, ongoing QT reducing US bank liquidity and its implications for banks’ ability to meet possible NDFI commitment drawdowns with on-balance sheet liquidity was not evaluated. It is true that banks can use off-balance sheet liquidity but it must be borrowed and paid for which reduces profitability.

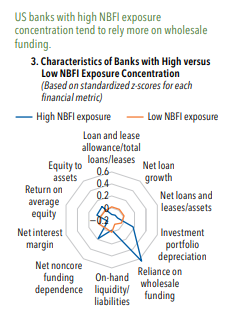

· Fourth, there is a limited scope to the CCAR-covered bank universe. Specifically, a number of US banks with high NDFI exposures relative to capital are not CCAR-covered, also have more fragile funding than their lower-exposure peers, have weaker on-balance sheet liquidity, and also have opted out of AOCI/AFS gains/losses in capital or are active users of CRT and SRT transactions which can reduce their ability to absorb loss relative to their headline risk-based regulatory capital ratios.

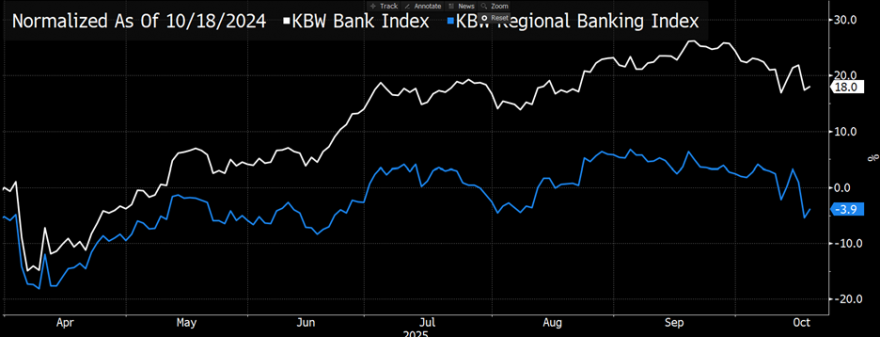

· It is difficult to look at the list of US banks with high NDFI exposures and not observe the impact of the US’ asset-size based regulatory and supervisory “tailoring” encouraging some mid-size institutions to take risks. Regional bank equity performance has now decoupled from the largest US banks and turned negative for the year.

Looking beyond CCAR, the IMF’s October 2025 Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) offered a short independent assessment of potential risks to advanced economy banking sectors, including U.S. banks (see pg 23-24). Fund staff’s GFSR stress analysis on NDFI risk was significantly more comprehensive than CCAR. The Fund’s analysis considered both bank capital and liquidity and, in the case of US banks, considered all banks with assets > $10 billion and who file data on NDFI exposures in US bank regulatory filings.

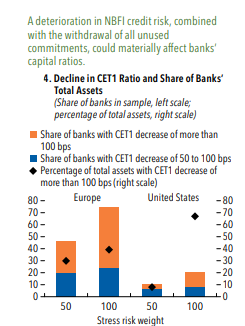

· In their analysis, IMF staff considered a migration in banks’ NDFI risk weight from 20% to 50% due to deteriorating credit quality and both 50% and 100% drawdown of all NDFI contingent lines and commitments.

· In light of these assumptions, Fund staff estimated that CET1 ratios would decline by more than 100 bps for about 10% of US banks with assets > $10 billion and 30% of European banks in the transition to a 50% risk-weight scenario.

· Fund staff estimate that banks totaling about 70% of US banking system assets would experience a decline in CET1 exceeding 100 bps if the risk weight of NDFIs transitioned to 100 percent. This implies meaningful shocks to large US banks but, like CCAR, still leaves unanswered how much these banks’ leverage ratios might worsen and interaction effects with unrealized interest rate losses at US banks which often do not flow through to regulatory capital.

While it would be helpful to know more about Fund staff’s definition of wholesale funding, Fund staff note that US banks with high NDFI exposure have greater reliance on wholesale funding and greater unrealized securities losses (investment portfolio depreciation).

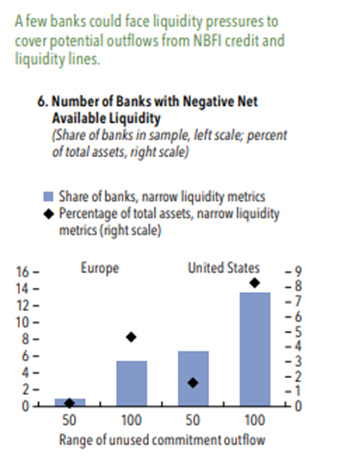

Going beyond CCAR’s overly narrow focus on capital, Fund staff also consider the adequacy of US banks’ on-balance sheet liquidity if NDFI credit lines are drawn and find this lacking at 6-12 US banks depending on the severity of NDFI drawdowns.

This is a useful contribution. However, as the 2008 crisis showed that liquidity strains are usually broad-based – affecting funding, repo market access, even deposits — and not limited just to a single factor like the drawdown of lines. So this analysis — while helpful — is a lower bound on US bank liquidity risks related to NDFIs. It also utilized Q2 regulatory data. Bank liquidity has been declining in Q3 due to ongoing QT reducing banking system reserves at the Fed.

Maybe the risks to US regional banks can be summed up even more simply.

· We still have some meaningful unresolved interest rate risk problems at some banks which both reduce profitability and reduce tangible capital.

· Now both tighter liquidity and credit and liquidity risk from NDFIs are showing up on the scene. Creepy!

Can we still have a happy Halloween and avoid a nightmare on ALM street? Let’s wrap up with some thoughts on what the official sector and banks can do from here.

The official sector

· Immediately end QT – this alleviates growing pressure on bank and funding market liquidity and potential pressure on NDFI funding models. Evaluate whether usable on-balance sheet banking sector liquidity may have been over-tightened, particularly in light of US banks still holding securities with over $400 billion in unrealized losses.

· Immediately close the Fed’s ON RRP – the Fed does not control the composition of its liabilities – reserves at banks vs money fund balances in ON RRP. Growth in the ON RRP occurred shortly before SVB failed as Fed rate expectations turned more hawkish. It could happen again. Fiscal stimulus and lower immigration could keep inflation and policy rates higher for longer. It is wise to take the risk of sharp ON RRP growth/banking system reserve drainage off the table.

· Strengthen operations of the discount window – ensure that knowledgeable discount window staff are available and evaluate how to quickly improve the existing automated access that some US banks report does not work well.

· Increase the US deposit insurance limit quickly — Increase the deposit insurance limit from $250K to $10 million per the proposed Hagerty bill. I recognize that some community banks feel that they do not benefit from higher deposit insurance thresholds to the same degree as regional banks. Deposit insurance, however, helps prevent contagious bank runs and thus can benefit all banks. Small businesses are ineffective in monitoring banks’ credit health and exercising market discipline. Discipline needs to be exercised through credible supervision and regulation and bank bondholders.

· Be cautious about large Fed rate cuts. I continue to believe that above target inflation and coming fiscal stimulus in early 2026 make for a weak case for further Fed rate cuts. However in addition to the macro outlook, advocates for large Fed rate cuts also should consider how growth in NDFIs’ corporate lending may have changed monetary policy transmission. While rate cuts are typically viewed both within and outside the Fed as providing accommodation, a significantly lower interest rate environment and steeper Treasury curve could lower corporate-oriented (BDCs, private credit) NDFI asset values, result in NDFI credit rating downgrades, and exacerbate NDFI funding difficulties. Ironically, large and rapid Fed rate cuts could crystallize the very shock that the official sector seek to guard against – namely, a shock to NDFIs’ middle mark.et/corporate lending with large negative spillovers to banks, corporates and US employment.

· Recognize that nothing changed after SVB and the spring of 2023. We continue to permit high levels of liquidity, interest rate risk and complexity at banks as a result of “tailored” regulation and supervision while also now putting forward proposals that encourage banks of all sizes to reduce capital. The US approach means that banks that are not deemed “systemic” in life can fall into trouble and quickly become systemic risks as they die which is what happened in the spring of 2023. Leveraged lending guidance enabled NDFI growth – not strong bank capital. Strong bank capital enables bank lending.

Bank teams

-

In ALCO carefully review the adequacy of on and off-balance sheet liquidity and term funding.

-

Check in and confirm your collateral with the Federal Home Loan Banks and the discount window. Touch base with contingent funding sources and check in on availability and terms.

-

Review covenants in your bank’s syndicate deals with NDFIs or covenants in loan agreements with corporates who also may have obtained NDFI finance.

-

Consider also a review of the quality of external auditors of NDFI and corporate obligors to help identify problem credits.

-

If you have high NDFI exposures, prepare your investor/market communication around them.

-

Review your bank’s stress analysis and understand your greatest vulnerabilities, including liquidity and solvency interactions at your institution.

-

Get ahead of any real or possible perceived weaknesses; don’t wait for the market to tell you to build your liquidity or capital or communicate more effectively about your strategy.

-

Be clear on your core crisis management team and overall approach within your bank to heightened condition monitoring.

For October FOMC, my expectations are a 25 bps cut and an end to QT.

Expressing hope that some of these reflections can help both policymakers and banks and wishing Treasury Talk readers a happy Halloween!

[1] To be fair the large US bank lobby – many of whom are former Fed economists — have sued the Fed on the construction of the CCAR stress tests. Such litigation is unlikely to yield a credible supervisory stress test which seems to be the point.